One of the beautiful things about the creation of The Great Sea is that it allows for a myriad of stories which have absolutely nothing to do with the Main Saga, which is Madatar's struggle to take possession of what was promised him.

There is a Troll story I want to tell, but that is probably going to become part of the Saga. There are tales from the Kingdom of Azua, but they indirectly point to the Saga, too.

But there are other worlds. Other creatures. Did you know that the Deltumler live in the ocean, and that their most hated enemy are the Sharogues? Both actually made an appearance in the original sequel to The Prophecies of Madatar, which was one of the Saga's earliest manifestations.

There are the Centaurs, the Pennans, the Nomads, and the orginal Men who populated the first giant world. And what of the Dragons and the Unicorns? At one time I thought about doing stories for all of these beings. Only I put it all on hold because I deemed the stories without a base if I could not get the Saga published.

The truth is, Apprentice and Quest could very easily take place on The Great Sea. Neither story has anything to do with Madatar.

Renaming this blog has reminded me that I have a host of stories to tell which are not based in any fashion or form upon the epic fantasy of my life's work.

The problem I have is I don't really understand online publishing at all, and that appears to be where short stories are going to have to be submitted in order to receive publication. Perhaps I should continue my Kiahva stories in hopes of finding a place for her. At the same time I could include a story or two about Dragons, Dwarfs, communities of Men on other worlds. All of this would build a base from which even the Saga could rise.

It's something to think about.

Showing posts with label Madatar-Ardora. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Madatar-Ardora. Show all posts

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

How Much is Too Much

If only Swords of Fire were published and available for everone to read. That would make posting about Madatar and Ardora easier. As it is, unpublished with only a bleak hope on the horizon of that ever changing, it is difficult for me to say much about them. You see, I don't want to say too much. I don't want to spill the beans, as it were. Knowledge about Madatar in particular is supposed to be progressive. But how can that be if I blab it all here? (Well, since nobody reads this, perhaps it doesn't matter.)

Last week I confessed that Madatar is revealed in Book II. What about Book I? Is Madatar there? Yes. Only we do not see him, hear him, or know what he is doing. Madatar is working from behind the scenes. Like every other character in Book I, Madatar is attempting to manipulate events to suit his purposes. It is not clear whether he is aware of Shatahar's plans to trap him at Khirsha's home village, but he does seem to possess a sense of urgency.

What I need, and have not had for years, is a regular confidant. I need someone to bounce ideas off to learn if they are any good. After I lost my original confidant I went for years alone. Then I thought I had found a new one. But she didn't want to learn about what was going to happen through discussing it with me. She wanted me to write it, so she could read and be surprised. She failed to understand my need to discuss both the future and the past in order to write the present. They are not separate stories. They are all part of the same flow and, as such, have to blend seemlessly into each other, the joining of hand to wrist to forearm to elbow to upper arm to shoulder. Each is a distinct part of the body, but there are no definitive lines separating them.

For now, take it that Madatar is very active in Book I, but hidden. Ardora is there, too. But she's even more hidden.

Last week I confessed that Madatar is revealed in Book II. What about Book I? Is Madatar there? Yes. Only we do not see him, hear him, or know what he is doing. Madatar is working from behind the scenes. Like every other character in Book I, Madatar is attempting to manipulate events to suit his purposes. It is not clear whether he is aware of Shatahar's plans to trap him at Khirsha's home village, but he does seem to possess a sense of urgency.

What I need, and have not had for years, is a regular confidant. I need someone to bounce ideas off to learn if they are any good. After I lost my original confidant I went for years alone. Then I thought I had found a new one. But she didn't want to learn about what was going to happen through discussing it with me. She wanted me to write it, so she could read and be surprised. She failed to understand my need to discuss both the future and the past in order to write the present. They are not separate stories. They are all part of the same flow and, as such, have to blend seemlessly into each other, the joining of hand to wrist to forearm to elbow to upper arm to shoulder. Each is a distinct part of the body, but there are no definitive lines separating them.

For now, take it that Madatar is very active in Book I, but hidden. Ardora is there, too. But she's even more hidden.

Posted by

Bevie

at

3:39 AM

Monday, December 22, 2008

What Exactly Do the Children of Fire Do

The Children of Fire (COF) did a good portion of the work during The Great Sea's creation. The Great Sea does not belong to them, however. Is this fair? No less fair than the fact that the men and women who did the actual construction of my house do not get to live here. At least the COF get to live on The Great Sea.

The COF are the most powerful beings on The Great Sea, excepting Madatar, Ardora and the High King, of course. As such, they have the power to do pretty much as they please. What they do not have is the authority. There is a limit on what the High King allows them to do. Up to that limit, it's mostly what they want. However, that being said, the High King has tasked them with certain duties. What the COF decide, individually and collectively, is whether to act in accordance with their duty. So what are the duties?

Mostly, the COF keep The Great Sea operating. They see to it that day and night remain on all inhabited worlds. They keep worlds on their course. They affect seasons. They have also been assigned the task of repairing The Great Sea. (After all, they were the ones who nearly destroyed it.) Basically, they are the custodial staff - masters of a variety of trades.

Hierarchically, there were four (4) levels: Lords (only Kensington, Draem and Zenophone); Wizards (the strongest); Teachers (less strong, but still formidable); Mortals (COF who chose to not only take physical form, but to accept mortality).

Not all the COF chose to comply with their duty. Some continued to seek domination, and they were given new names. Zenophone was still called a Lord, but the Wizards who abandoned their call were renamed Warlords. Teachers were called Titans and Mortals became Overlords. The Overlords extended their disobedience by taking Free People slaves and mating with them. From these unions came the Accursed Races: Gnomes, Barbarians, Renegades, Gargoyles - and Trolls.

Kensington, and his followers, maintained control of all The Great Sea's key elements, including Time. In fact, Kensington personally controlled the Regulator of Time. This was important, as history could not be changed once the Regulator of Time passed. (No world was 'in sync' with the Regulator of Time. In fact, they were all ahead of it.) Well, it was too difficult for most anyway.

Time is an important element in Swords of Fire. It is neither constant nor permanent. History can be changed - providing one has the power and means to go backward in Time. It is possible - on The Great Sea - to 'step out of Time'. Doing so presents all possibilities based on all possible choices. It is a dangerous venture, for one could find themself trapped 'outside of Time'. For this reason, the Free People were not granted this power naturally (like the COF). But using the power of Madatar they could do it, although only a couple did.

One final task the COF had was to support Madatar and Ardora. This Kensington, Draem and their followers did - one with particular zeal. Zenophone and his followers sought Madatar and Ardora's demise. They could not be 'killed' as we understand dying. But they could be so weakened they would be trapped on one of two isles made for COF who had become too weak to continue: the Isle of Wonder and the Isle of Nether Gloom.

Kensington and his followers continued to send messages to various members of the Free People, warning them of critical events in their path, such as storms, earthquakes, famine and such. Not everyone could hear them (the COF used the winds to speak), and those who could generally could not hear just anyone. It was a long and arduous task to match a member of the COF with an individual who could hear and understand them. Those of the Free People who could became known as Prophets, and their ability was sometimes called The Gift. There were a few communities in which large percentages of the populous had this ability. This is hinted at in Books I and II, and reveals itself more fully in Book III.

The COF are the most powerful beings on The Great Sea, excepting Madatar, Ardora and the High King, of course. As such, they have the power to do pretty much as they please. What they do not have is the authority. There is a limit on what the High King allows them to do. Up to that limit, it's mostly what they want. However, that being said, the High King has tasked them with certain duties. What the COF decide, individually and collectively, is whether to act in accordance with their duty. So what are the duties?

Mostly, the COF keep The Great Sea operating. They see to it that day and night remain on all inhabited worlds. They keep worlds on their course. They affect seasons. They have also been assigned the task of repairing The Great Sea. (After all, they were the ones who nearly destroyed it.) Basically, they are the custodial staff - masters of a variety of trades.

Hierarchically, there were four (4) levels: Lords (only Kensington, Draem and Zenophone); Wizards (the strongest); Teachers (less strong, but still formidable); Mortals (COF who chose to not only take physical form, but to accept mortality).

Not all the COF chose to comply with their duty. Some continued to seek domination, and they were given new names. Zenophone was still called a Lord, but the Wizards who abandoned their call were renamed Warlords. Teachers were called Titans and Mortals became Overlords. The Overlords extended their disobedience by taking Free People slaves and mating with them. From these unions came the Accursed Races: Gnomes, Barbarians, Renegades, Gargoyles - and Trolls.

Kensington, and his followers, maintained control of all The Great Sea's key elements, including Time. In fact, Kensington personally controlled the Regulator of Time. This was important, as history could not be changed once the Regulator of Time passed. (No world was 'in sync' with the Regulator of Time. In fact, they were all ahead of it.) Well, it was too difficult for most anyway.

Time is an important element in Swords of Fire. It is neither constant nor permanent. History can be changed - providing one has the power and means to go backward in Time. It is possible - on The Great Sea - to 'step out of Time'. Doing so presents all possibilities based on all possible choices. It is a dangerous venture, for one could find themself trapped 'outside of Time'. For this reason, the Free People were not granted this power naturally (like the COF). But using the power of Madatar they could do it, although only a couple did.

One final task the COF had was to support Madatar and Ardora. This Kensington, Draem and their followers did - one with particular zeal. Zenophone and his followers sought Madatar and Ardora's demise. They could not be 'killed' as we understand dying. But they could be so weakened they would be trapped on one of two isles made for COF who had become too weak to continue: the Isle of Wonder and the Isle of Nether Gloom.

Kensington and his followers continued to send messages to various members of the Free People, warning them of critical events in their path, such as storms, earthquakes, famine and such. Not everyone could hear them (the COF used the winds to speak), and those who could generally could not hear just anyone. It was a long and arduous task to match a member of the COF with an individual who could hear and understand them. Those of the Free People who could became known as Prophets, and their ability was sometimes called The Gift. There were a few communities in which large percentages of the populous had this ability. This is hinted at in Books I and II, and reveals itself more fully in Book III.

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

If the Saga's About Madatar, Why Make Khirsha the Main Character

Swords of Fire is about Madatar. It is his story. But he is not the Point of View Character (POVC). Neither is Ardora, the Yin to to his Yang. Instead, the POVC is a character who is young, strong, vulnerable and who has a lot to learn. Why?

Mostly, it felt right. But there are clear advantages in choosing Khirsha over Madatar. The most important being that the reader gets to discover Madatar over time - like all the other characters in Swords of Fire. Until Madatar is revealed (in Book II, if you're interested), we wonder about him. Who is he, really? Why hasn't he revealed himself - to anyone?

There are clues but, like so many clues, they don't appear to be clues until shortly before (or after) their revelation. There were more clues, but I'm being forced to cut some in order to shorten the length of Book I. Even after Madatar is revealed, we are left with things to ponder. Each book in the progression presents new clues, and our knowledge escalates with the conflict until the inevitable final battle. (I haven't written it - officially - but I know what it is.)

Actually, did I say the most important reason for choosing Khirsha instead of Madatar as POVC was to discover Madatar? I'm wrong. The most important reason is that I believe readers can better identify with Khirsha than with Madatar. Khirsha is more like us. He lives in a physical world, as opposed to the spirit realm of Madatar and the Children of Fire. Khirsha is a lot like us - even if he isn't.

Mostly, it felt right. But there are clear advantages in choosing Khirsha over Madatar. The most important being that the reader gets to discover Madatar over time - like all the other characters in Swords of Fire. Until Madatar is revealed (in Book II, if you're interested), we wonder about him. Who is he, really? Why hasn't he revealed himself - to anyone?

There are clues but, like so many clues, they don't appear to be clues until shortly before (or after) their revelation. There were more clues, but I'm being forced to cut some in order to shorten the length of Book I. Even after Madatar is revealed, we are left with things to ponder. Each book in the progression presents new clues, and our knowledge escalates with the conflict until the inevitable final battle. (I haven't written it - officially - but I know what it is.)

Actually, did I say the most important reason for choosing Khirsha instead of Madatar as POVC was to discover Madatar? I'm wrong. The most important reason is that I believe readers can better identify with Khirsha than with Madatar. Khirsha is more like us. He lives in a physical world, as opposed to the spirit realm of Madatar and the Children of Fire. Khirsha is a lot like us - even if he isn't.

Posted by

Bevie

at

4:04 AM

Sunday, December 14, 2008

The High King - Good or Evil

I suppose the definition of the High King's involvement in The Great Sea depends on one's view of someone who has the power to do anything. Most views of such beings - real or imagined - tend to be prejudiced one way or the other.

Some would hold that, since the High King has the power to stop all evil but doesn't, the High King is himself evil. They maintain that a good being of such power would suppress all evil and keep The Great Sea at peace. But there is a problem with that which the Evil Viewers (those who see the High King as evil, not viewers who are evil) refuse to acknowledge. In order to suppress all evil, the High King (or whoever) would have to suppress all freedom, because the simple truth is - everyone tends to evil. The Evil Viewers deny this, but it is true. All beings, creatures and what have you are inclined to act out of selfish motive. Not only that, but what one being, creature or what have you considers evil, another might consider their 'right', and to be denied that right is evil. You see, it comes down to how one defines evil. Let us look at The Great Sea.

The High King created The Great Sea. It was his to give to whomever he chose. He gave it to the Children of Fire, but with the understanding it was eventually to go to Madatar and Ardora. Until Madatar and Ardora claimed their gift, Kensington was to rule and Draem and Zenophone were to support him. Fair enough.

But in Zenophone's mind, he was far better suited to rule the Sea than Kensington. Furthermore, why should the Sea be given to Madatar and Ardora when they had no part in fashioning it? After all, was it not the Children who did most of the actual work? In Zenophone's mind, it was evil for him to do all of that work and get nothing in reward. It wasn't fair that Madatar and Ardora should be given something for which they had not labored. Evil.

From Kensington's point of view it did not matter that Madatar had not been present. The Sea belonged to the High King and the High King was free to give it to whomever he wished. It could be argued that being given the regency may have influenced Kensington's thinking. Would he have thought the same had Zenophone been chosen as regent? In any case, from Kensington's point of view, refusal to abide by the High King's decision was evil.

But it goes even further than that. The concept of what is evil and what is good filters down into the very basic elements which make up life on the Sea. The mortal beings who have been given free thought - and thus named Free People - have dominion over the creatures which live out their existence by instinct. Horses, sheep, cattle and other creatures are forced to serve Men, Dwarfs and Figgits. Is that fair? What is more, some creatures live by feeding upon others. Is that fair? Some say yes and some say no.

The High King set the rules by allowing certain things to be and not others. Individual concepts of his goodness - or lack of it - derive from a selfish perspective. The free thinking beings considered actions which supported their wants and desires to be good, and those which interfered with them bad. Beasts and other creatures didn't care one way or another. They just lived until they died, and perhaps that is the pivitol point on which good and evil truly separate. There is life, and then there is death. What happens after death? Nothing? Transition? Eternity? What happens?

If, as some claimed, death was the end of whatever/whoever died, then life on The Great Sea was all important, and whatever happened on The Great Sea was all important. So to be denied a good life for no apparent reason was evil.

But what if there was more? What if life on The Great Sea was akin to living in a nursery? What if dying simply meant graduation? That changes things a bit, although there are those who would say not by much. But suddenly, life on The Great Sea becomes a school. Troubles and blessings, whether one's own or another's, are simply lessons to help prepare for what comes next. If so, then why not just say what comes next? Maybe because what comes next is entirely determined by what takes place? It changes things drastically, at least in the minds of some.

Was the High King good or bad? Each reader will make up his/her own mind regarding that, and that is as it should be. Some will express their opinion to others, and that is well and good. Others may even seek to persuade others to believe as they do, which is fine. Some will get angry when others disagree with them. That is unfortunate.

In any case, what is the Author's intent? Well, that would be me. With regard to Swords of Fire, I am the one who has the power to put a stop to anything I choose. Even the High King cannot act apart from my will. As a writer, I make the determination over what is good, what is bad - and what is simply a matter of perspective. When someone reads what I have written, the story becomes their's, and they will make these determinations.

For the record, I believe the High King is good - because he conforms to my idea of goodness. However, even I must concede that he cannot be wholly good, because my idea of goodness tends to be somewhat fluid, changing as I grow in knowledge and experience. It isn't runny, like pure water. It is more like a thick lava crawling across the ground. It will harden in time, but that is not to say a great upheaval cannot change it.

So it is with me. Many of my beliefs regarding good and bad have hardened. Not all. New experience still affects my views on many things, and in some things I have completely reversed my thinking over the years. This is especially so in areas involving punishment and forgiveness. I don't see far, but I see further ahead than I did before. My physical eyes continue to weaken, but my inner eyes, my comprehension, increase, albeit slowly. As I understand better, I can see further ahead - to a point. This is affecting how I view good and bad and punishment and forgiveness. I see myself differently, and so I see others differently. I don't always like what I see in me, but I'm realizing I am so much like everyone else - even if I am so different.

Is the High King good? Of course he is, silly. He is me. How can I see him any other way?

Some would hold that, since the High King has the power to stop all evil but doesn't, the High King is himself evil. They maintain that a good being of such power would suppress all evil and keep The Great Sea at peace. But there is a problem with that which the Evil Viewers (those who see the High King as evil, not viewers who are evil) refuse to acknowledge. In order to suppress all evil, the High King (or whoever) would have to suppress all freedom, because the simple truth is - everyone tends to evil. The Evil Viewers deny this, but it is true. All beings, creatures and what have you are inclined to act out of selfish motive. Not only that, but what one being, creature or what have you considers evil, another might consider their 'right', and to be denied that right is evil. You see, it comes down to how one defines evil. Let us look at The Great Sea.

The High King created The Great Sea. It was his to give to whomever he chose. He gave it to the Children of Fire, but with the understanding it was eventually to go to Madatar and Ardora. Until Madatar and Ardora claimed their gift, Kensington was to rule and Draem and Zenophone were to support him. Fair enough.

But in Zenophone's mind, he was far better suited to rule the Sea than Kensington. Furthermore, why should the Sea be given to Madatar and Ardora when they had no part in fashioning it? After all, was it not the Children who did most of the actual work? In Zenophone's mind, it was evil for him to do all of that work and get nothing in reward. It wasn't fair that Madatar and Ardora should be given something for which they had not labored. Evil.

From Kensington's point of view it did not matter that Madatar had not been present. The Sea belonged to the High King and the High King was free to give it to whomever he wished. It could be argued that being given the regency may have influenced Kensington's thinking. Would he have thought the same had Zenophone been chosen as regent? In any case, from Kensington's point of view, refusal to abide by the High King's decision was evil.

But it goes even further than that. The concept of what is evil and what is good filters down into the very basic elements which make up life on the Sea. The mortal beings who have been given free thought - and thus named Free People - have dominion over the creatures which live out their existence by instinct. Horses, sheep, cattle and other creatures are forced to serve Men, Dwarfs and Figgits. Is that fair? What is more, some creatures live by feeding upon others. Is that fair? Some say yes and some say no.

The High King set the rules by allowing certain things to be and not others. Individual concepts of his goodness - or lack of it - derive from a selfish perspective. The free thinking beings considered actions which supported their wants and desires to be good, and those which interfered with them bad. Beasts and other creatures didn't care one way or another. They just lived until they died, and perhaps that is the pivitol point on which good and evil truly separate. There is life, and then there is death. What happens after death? Nothing? Transition? Eternity? What happens?

If, as some claimed, death was the end of whatever/whoever died, then life on The Great Sea was all important, and whatever happened on The Great Sea was all important. So to be denied a good life for no apparent reason was evil.

But what if there was more? What if life on The Great Sea was akin to living in a nursery? What if dying simply meant graduation? That changes things a bit, although there are those who would say not by much. But suddenly, life on The Great Sea becomes a school. Troubles and blessings, whether one's own or another's, are simply lessons to help prepare for what comes next. If so, then why not just say what comes next? Maybe because what comes next is entirely determined by what takes place? It changes things drastically, at least in the minds of some.

Was the High King good or bad? Each reader will make up his/her own mind regarding that, and that is as it should be. Some will express their opinion to others, and that is well and good. Others may even seek to persuade others to believe as they do, which is fine. Some will get angry when others disagree with them. That is unfortunate.

In any case, what is the Author's intent? Well, that would be me. With regard to Swords of Fire, I am the one who has the power to put a stop to anything I choose. Even the High King cannot act apart from my will. As a writer, I make the determination over what is good, what is bad - and what is simply a matter of perspective. When someone reads what I have written, the story becomes their's, and they will make these determinations.

For the record, I believe the High King is good - because he conforms to my idea of goodness. However, even I must concede that he cannot be wholly good, because my idea of goodness tends to be somewhat fluid, changing as I grow in knowledge and experience. It isn't runny, like pure water. It is more like a thick lava crawling across the ground. It will harden in time, but that is not to say a great upheaval cannot change it.

So it is with me. Many of my beliefs regarding good and bad have hardened. Not all. New experience still affects my views on many things, and in some things I have completely reversed my thinking over the years. This is especially so in areas involving punishment and forgiveness. I don't see far, but I see further ahead than I did before. My physical eyes continue to weaken, but my inner eyes, my comprehension, increase, albeit slowly. As I understand better, I can see further ahead - to a point. This is affecting how I view good and bad and punishment and forgiveness. I see myself differently, and so I see others differently. I don't always like what I see in me, but I'm realizing I am so much like everyone else - even if I am so different.

Is the High King good? Of course he is, silly. He is me. How can I see him any other way?

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Madatar and Ardora

Madatar was part of the original creation - both mine, and the High King's. Who and what he was grew as I continued to write until he became the one for whom the Great Sea was created.

Ardora is a more recent, but logical, creation - mine, NOT the High King's. Ardora began when Madatar began. She is the compliment to Madatar - the Yin to his Yang.

Madatar and Ardora are also beings of Fire. Spirits, if you will, but of a different order than the other Children of Fire. Individually, they became more powerful than any other on the Great Sea, save the High King himself. Collectively, they became more powerful than everyone, and everything, combined on the Great Sea, save the High King. But they are not together.

Shortly after the Great Sea's creation, Zenophone and his followers attempted to take the Great Sea for their own. Ultimately this resulted in the Great War, in which the Sea itself was nearly destroyed. It was at this time Madatar and Ardora were separated and hid from each other. For while they were destined to become the reigning power over the Great Sea, they had yet to achieve that stature. In the early days of the Sea's history they were vulnerable. So the High King hid them, and not even Kensington knew where.

Why would the High King separate them? It is not always easy to know the thoughts of the High King. But this we know: Even at the Beginning, Madatar nor Ardora did not have the power to defeat Zenophone and his followers. However, together their growth would cause ripples across the Sea which would only draw their enemies to them. Separated, the ripples became confused with all else that was taking place.

That is the story of Swords of Fire. It is the saga of Madatar and Ardora's search for each other and their ultimate battle with Zenophone and his followers. It is presented from the perspective of one Khirsha, son of Klarissa and Shello, of the Line of Swords, in the House of Jora. Khirsha became the eye of the storm, so to speak.

Ardora is a more recent, but logical, creation - mine, NOT the High King's. Ardora began when Madatar began. She is the compliment to Madatar - the Yin to his Yang.

Madatar and Ardora are also beings of Fire. Spirits, if you will, but of a different order than the other Children of Fire. Individually, they became more powerful than any other on the Great Sea, save the High King himself. Collectively, they became more powerful than everyone, and everything, combined on the Great Sea, save the High King. But they are not together.

Shortly after the Great Sea's creation, Zenophone and his followers attempted to take the Great Sea for their own. Ultimately this resulted in the Great War, in which the Sea itself was nearly destroyed. It was at this time Madatar and Ardora were separated and hid from each other. For while they were destined to become the reigning power over the Great Sea, they had yet to achieve that stature. In the early days of the Sea's history they were vulnerable. So the High King hid them, and not even Kensington knew where.

Why would the High King separate them? It is not always easy to know the thoughts of the High King. But this we know: Even at the Beginning, Madatar nor Ardora did not have the power to defeat Zenophone and his followers. However, together their growth would cause ripples across the Sea which would only draw their enemies to them. Separated, the ripples became confused with all else that was taking place.

That is the story of Swords of Fire. It is the saga of Madatar and Ardora's search for each other and their ultimate battle with Zenophone and his followers. It is presented from the perspective of one Khirsha, son of Klarissa and Shello, of the Line of Swords, in the House of Jora. Khirsha became the eye of the storm, so to speak.

Posted by

Bevie

at

1:48 AM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

High King,

Madatar-Ardora,

Saga Elements

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Today's Music

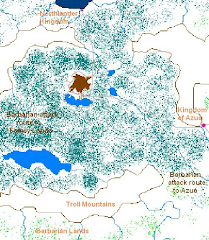

Yeah. That's The Great Sea all right.