Back in December I posted about the Religious Message intended with Swords of Fire. Basically, none is.

All the same, it is difficult to create a world like The Great Sea without including elements which many would consider religious. Foremost among these elements is the idea of creation, and a Creator.

It turns some people off completely. Others are drawn by exactly those elements. And still others (probably most) don't care one way or the other. It's just part of the story.

I suppose it is difficult for a writer to not impart his/her basic beliefs into their writing, even when writing outside their basic beliefs. My beliefs on good and evil are reflected in what I write, for when characters behave in a certain way they are written as "evil" characters. And when characters behave in another way they are written as "noble".

What is difficult - if not outright impossible - is to write God as a character in a story. I've seen it done on movies and television shows, and read it in various other works. NEVER is God's character believable. God is not petty. God is not stupid. God is not ignorant. God does not make mistakes. And God does not answer to us.

I suppose that is why the High King in Swords of Fire is never a physically present character. He is referenced, and perhaps even spoke to. But he never speaks back. Not audibly to the characters. Determining what God would say is not easy to determine, and so often best left unsaid in fiction. Besides, to make the High King a more present character in Swords of Fire would only increase the presence of religion, I think. And I would just as soon avoid that for now. I'm not qualified to write religion. Not yet.

Showing posts with label High King. Show all posts

Showing posts with label High King. Show all posts

Sunday, February 22, 2009

Monday, December 22, 2008

What Exactly Do the Children of Fire Do

The Children of Fire (COF) did a good portion of the work during The Great Sea's creation. The Great Sea does not belong to them, however. Is this fair? No less fair than the fact that the men and women who did the actual construction of my house do not get to live here. At least the COF get to live on The Great Sea.

The COF are the most powerful beings on The Great Sea, excepting Madatar, Ardora and the High King, of course. As such, they have the power to do pretty much as they please. What they do not have is the authority. There is a limit on what the High King allows them to do. Up to that limit, it's mostly what they want. However, that being said, the High King has tasked them with certain duties. What the COF decide, individually and collectively, is whether to act in accordance with their duty. So what are the duties?

Mostly, the COF keep The Great Sea operating. They see to it that day and night remain on all inhabited worlds. They keep worlds on their course. They affect seasons. They have also been assigned the task of repairing The Great Sea. (After all, they were the ones who nearly destroyed it.) Basically, they are the custodial staff - masters of a variety of trades.

Hierarchically, there were four (4) levels: Lords (only Kensington, Draem and Zenophone); Wizards (the strongest); Teachers (less strong, but still formidable); Mortals (COF who chose to not only take physical form, but to accept mortality).

Not all the COF chose to comply with their duty. Some continued to seek domination, and they were given new names. Zenophone was still called a Lord, but the Wizards who abandoned their call were renamed Warlords. Teachers were called Titans and Mortals became Overlords. The Overlords extended their disobedience by taking Free People slaves and mating with them. From these unions came the Accursed Races: Gnomes, Barbarians, Renegades, Gargoyles - and Trolls.

Kensington, and his followers, maintained control of all The Great Sea's key elements, including Time. In fact, Kensington personally controlled the Regulator of Time. This was important, as history could not be changed once the Regulator of Time passed. (No world was 'in sync' with the Regulator of Time. In fact, they were all ahead of it.) Well, it was too difficult for most anyway.

Time is an important element in Swords of Fire. It is neither constant nor permanent. History can be changed - providing one has the power and means to go backward in Time. It is possible - on The Great Sea - to 'step out of Time'. Doing so presents all possibilities based on all possible choices. It is a dangerous venture, for one could find themself trapped 'outside of Time'. For this reason, the Free People were not granted this power naturally (like the COF). But using the power of Madatar they could do it, although only a couple did.

One final task the COF had was to support Madatar and Ardora. This Kensington, Draem and their followers did - one with particular zeal. Zenophone and his followers sought Madatar and Ardora's demise. They could not be 'killed' as we understand dying. But they could be so weakened they would be trapped on one of two isles made for COF who had become too weak to continue: the Isle of Wonder and the Isle of Nether Gloom.

Kensington and his followers continued to send messages to various members of the Free People, warning them of critical events in their path, such as storms, earthquakes, famine and such. Not everyone could hear them (the COF used the winds to speak), and those who could generally could not hear just anyone. It was a long and arduous task to match a member of the COF with an individual who could hear and understand them. Those of the Free People who could became known as Prophets, and their ability was sometimes called The Gift. There were a few communities in which large percentages of the populous had this ability. This is hinted at in Books I and II, and reveals itself more fully in Book III.

The COF are the most powerful beings on The Great Sea, excepting Madatar, Ardora and the High King, of course. As such, they have the power to do pretty much as they please. What they do not have is the authority. There is a limit on what the High King allows them to do. Up to that limit, it's mostly what they want. However, that being said, the High King has tasked them with certain duties. What the COF decide, individually and collectively, is whether to act in accordance with their duty. So what are the duties?

Mostly, the COF keep The Great Sea operating. They see to it that day and night remain on all inhabited worlds. They keep worlds on their course. They affect seasons. They have also been assigned the task of repairing The Great Sea. (After all, they were the ones who nearly destroyed it.) Basically, they are the custodial staff - masters of a variety of trades.

Hierarchically, there were four (4) levels: Lords (only Kensington, Draem and Zenophone); Wizards (the strongest); Teachers (less strong, but still formidable); Mortals (COF who chose to not only take physical form, but to accept mortality).

Not all the COF chose to comply with their duty. Some continued to seek domination, and they were given new names. Zenophone was still called a Lord, but the Wizards who abandoned their call were renamed Warlords. Teachers were called Titans and Mortals became Overlords. The Overlords extended their disobedience by taking Free People slaves and mating with them. From these unions came the Accursed Races: Gnomes, Barbarians, Renegades, Gargoyles - and Trolls.

Kensington, and his followers, maintained control of all The Great Sea's key elements, including Time. In fact, Kensington personally controlled the Regulator of Time. This was important, as history could not be changed once the Regulator of Time passed. (No world was 'in sync' with the Regulator of Time. In fact, they were all ahead of it.) Well, it was too difficult for most anyway.

Time is an important element in Swords of Fire. It is neither constant nor permanent. History can be changed - providing one has the power and means to go backward in Time. It is possible - on The Great Sea - to 'step out of Time'. Doing so presents all possibilities based on all possible choices. It is a dangerous venture, for one could find themself trapped 'outside of Time'. For this reason, the Free People were not granted this power naturally (like the COF). But using the power of Madatar they could do it, although only a couple did.

One final task the COF had was to support Madatar and Ardora. This Kensington, Draem and their followers did - one with particular zeal. Zenophone and his followers sought Madatar and Ardora's demise. They could not be 'killed' as we understand dying. But they could be so weakened they would be trapped on one of two isles made for COF who had become too weak to continue: the Isle of Wonder and the Isle of Nether Gloom.

Kensington and his followers continued to send messages to various members of the Free People, warning them of critical events in their path, such as storms, earthquakes, famine and such. Not everyone could hear them (the COF used the winds to speak), and those who could generally could not hear just anyone. It was a long and arduous task to match a member of the COF with an individual who could hear and understand them. Those of the Free People who could became known as Prophets, and their ability was sometimes called The Gift. There were a few communities in which large percentages of the populous had this ability. This is hinted at in Books I and II, and reveals itself more fully in Book III.

Sunday, December 21, 2008

So What is the 'Religious' Message

There isn't one. Not officially. However, I remember giving the book to a co-worker a few years back. She liked to read fantasy, and she was very intelligent, so when she expressed an interest in reading what I had written I told her I would be pleased to hear what she had to say about it.

She only came back with two comments. The first was I had a tendency to shift the Point of View (POV). I thought I had corrected that, but I even got called on it from the Minions when I submitted my first 300 words to Evil Editor (http://evileditor.blogspot.com). The second was that it was "too religious" for her to get into. I argued that it wasn't relgious at all, but she wouldn't accept it.

I felt bad because she wasn't going to read it again or give me any more help, but I wasn't going to change the story just because she thought it was religious. For one thing, I still didn't think it was. I certainly had no conscious intent, anyway.

Afterward, I tried to figure out why she thought the book was religous. (She didn't want to talk about it.) My only conclusions - right or wrong, I'll never know - were my references to the High King, and that The Great Sea as a created place (suggesting God). Oh, and I supposed she thought Zenophone was Satan. I don't know who she thought was Jesus Christ. There is no Christ figure in the book. None of my characters are without fault, much less sinless. Characters may sacrifice themselves for other characters, but that is true on both sides of the fight. The Barbarians are as likely to sacrifice themselves for their comrades as anyone in Khirsha's family. The point of the book is not about getting to heaven, or being reconciled with the High King. It is about the struggle for control of a place, called The Great Sea. To me, it's not religous.

I think the problem was that Jenni didn't like it that 'religion' was against some things which were part of her lifestyle, and so she was ever alert to defend herself against charges of sin. I didn't put any of that in the book. The book isn't about telling people what's right and what's wrong, or what they should think or believe. When I was young I tried to write like that, but all of that writing was contrived crap. As I have aged I have come to realize nobody has charged me with the task of making anyone believe anything. Those are not the gifts I was given at birth. What I am good at, and what I enjoy doing, is telling stories. That's what Swords of Fire is: a story. And I want the characters to seem real, so every character has both admirable - and not so admirable - traits.

Swords of Fire is not some kind of cheap instruction manual on morality. (You won't get through Book I before you realize my main characters are far from being Champions of Morality.) It is history. It is what happened at a place called, The Great Sea. No brow beating intended. I promise. But I couldn't make Jenni understand that.

All the same, I now believe I was wrong to argue with Jenni about what she got from my book. It is my feeling that when a reader reads a story, it becomes theirs, and they are a free to take from it whatever they wish. I denied Jenni that right, and maybe that's more why she was finished with the book. We were still friends. We talked and laughed about other things, confiding what co-workers confide. But we couldn't talk about the book anymore.

That I have 'religious' (I hate that word) convictions is no surprise. Most people have them. Even believing there is no God is a religious conviction, I think. And I guess it is only a matter of course that what I believe works its way into what I write - particularly as regards fiction. My concepts of good and bad show in some of the family laws/edicts. Most of what I believe to be 'good' and most of what I believe to be 'bad' is shared by most of the people who share my culture. In Swords of Fire, even the so-called 'good' cultures adhere to rules and behavior I do not consider good in my own culture. The same is true for bad. So either I'm a hyprocrite, or I'm not so solid in my convictions as I believe, or it doesn't matter at all because Swords of Fire is just a story. It's a safe exploration of other ways of thinking. I don't know. I think that's too deep for me.

So here's the short answer: Swords of Fire is a story. Take from it what you will. I do hope you enjoy it. That, I did intend.

She only came back with two comments. The first was I had a tendency to shift the Point of View (POV). I thought I had corrected that, but I even got called on it from the Minions when I submitted my first 300 words to Evil Editor (http://evileditor.blogspot.com). The second was that it was "too religious" for her to get into. I argued that it wasn't relgious at all, but she wouldn't accept it.

I felt bad because she wasn't going to read it again or give me any more help, but I wasn't going to change the story just because she thought it was religious. For one thing, I still didn't think it was. I certainly had no conscious intent, anyway.

Afterward, I tried to figure out why she thought the book was religous. (She didn't want to talk about it.) My only conclusions - right or wrong, I'll never know - were my references to the High King, and that The Great Sea as a created place (suggesting God). Oh, and I supposed she thought Zenophone was Satan. I don't know who she thought was Jesus Christ. There is no Christ figure in the book. None of my characters are without fault, much less sinless. Characters may sacrifice themselves for other characters, but that is true on both sides of the fight. The Barbarians are as likely to sacrifice themselves for their comrades as anyone in Khirsha's family. The point of the book is not about getting to heaven, or being reconciled with the High King. It is about the struggle for control of a place, called The Great Sea. To me, it's not religous.

I think the problem was that Jenni didn't like it that 'religion' was against some things which were part of her lifestyle, and so she was ever alert to defend herself against charges of sin. I didn't put any of that in the book. The book isn't about telling people what's right and what's wrong, or what they should think or believe. When I was young I tried to write like that, but all of that writing was contrived crap. As I have aged I have come to realize nobody has charged me with the task of making anyone believe anything. Those are not the gifts I was given at birth. What I am good at, and what I enjoy doing, is telling stories. That's what Swords of Fire is: a story. And I want the characters to seem real, so every character has both admirable - and not so admirable - traits.

Swords of Fire is not some kind of cheap instruction manual on morality. (You won't get through Book I before you realize my main characters are far from being Champions of Morality.) It is history. It is what happened at a place called, The Great Sea. No brow beating intended. I promise. But I couldn't make Jenni understand that.

All the same, I now believe I was wrong to argue with Jenni about what she got from my book. It is my feeling that when a reader reads a story, it becomes theirs, and they are a free to take from it whatever they wish. I denied Jenni that right, and maybe that's more why she was finished with the book. We were still friends. We talked and laughed about other things, confiding what co-workers confide. But we couldn't talk about the book anymore.

That I have 'religious' (I hate that word) convictions is no surprise. Most people have them. Even believing there is no God is a religious conviction, I think. And I guess it is only a matter of course that what I believe works its way into what I write - particularly as regards fiction. My concepts of good and bad show in some of the family laws/edicts. Most of what I believe to be 'good' and most of what I believe to be 'bad' is shared by most of the people who share my culture. In Swords of Fire, even the so-called 'good' cultures adhere to rules and behavior I do not consider good in my own culture. The same is true for bad. So either I'm a hyprocrite, or I'm not so solid in my convictions as I believe, or it doesn't matter at all because Swords of Fire is just a story. It's a safe exploration of other ways of thinking. I don't know. I think that's too deep for me.

So here's the short answer: Swords of Fire is a story. Take from it what you will. I do hope you enjoy it. That, I did intend.

Posted by

Bevie

at

6:37 AM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

Culture,

High King,

Khirsha and His Family

Sunday, December 14, 2008

The High King - Good or Evil

I suppose the definition of the High King's involvement in The Great Sea depends on one's view of someone who has the power to do anything. Most views of such beings - real or imagined - tend to be prejudiced one way or the other.

Some would hold that, since the High King has the power to stop all evil but doesn't, the High King is himself evil. They maintain that a good being of such power would suppress all evil and keep The Great Sea at peace. But there is a problem with that which the Evil Viewers (those who see the High King as evil, not viewers who are evil) refuse to acknowledge. In order to suppress all evil, the High King (or whoever) would have to suppress all freedom, because the simple truth is - everyone tends to evil. The Evil Viewers deny this, but it is true. All beings, creatures and what have you are inclined to act out of selfish motive. Not only that, but what one being, creature or what have you considers evil, another might consider their 'right', and to be denied that right is evil. You see, it comes down to how one defines evil. Let us look at The Great Sea.

The High King created The Great Sea. It was his to give to whomever he chose. He gave it to the Children of Fire, but with the understanding it was eventually to go to Madatar and Ardora. Until Madatar and Ardora claimed their gift, Kensington was to rule and Draem and Zenophone were to support him. Fair enough.

But in Zenophone's mind, he was far better suited to rule the Sea than Kensington. Furthermore, why should the Sea be given to Madatar and Ardora when they had no part in fashioning it? After all, was it not the Children who did most of the actual work? In Zenophone's mind, it was evil for him to do all of that work and get nothing in reward. It wasn't fair that Madatar and Ardora should be given something for which they had not labored. Evil.

From Kensington's point of view it did not matter that Madatar had not been present. The Sea belonged to the High King and the High King was free to give it to whomever he wished. It could be argued that being given the regency may have influenced Kensington's thinking. Would he have thought the same had Zenophone been chosen as regent? In any case, from Kensington's point of view, refusal to abide by the High King's decision was evil.

But it goes even further than that. The concept of what is evil and what is good filters down into the very basic elements which make up life on the Sea. The mortal beings who have been given free thought - and thus named Free People - have dominion over the creatures which live out their existence by instinct. Horses, sheep, cattle and other creatures are forced to serve Men, Dwarfs and Figgits. Is that fair? What is more, some creatures live by feeding upon others. Is that fair? Some say yes and some say no.

The High King set the rules by allowing certain things to be and not others. Individual concepts of his goodness - or lack of it - derive from a selfish perspective. The free thinking beings considered actions which supported their wants and desires to be good, and those which interfered with them bad. Beasts and other creatures didn't care one way or another. They just lived until they died, and perhaps that is the pivitol point on which good and evil truly separate. There is life, and then there is death. What happens after death? Nothing? Transition? Eternity? What happens?

If, as some claimed, death was the end of whatever/whoever died, then life on The Great Sea was all important, and whatever happened on The Great Sea was all important. So to be denied a good life for no apparent reason was evil.

But what if there was more? What if life on The Great Sea was akin to living in a nursery? What if dying simply meant graduation? That changes things a bit, although there are those who would say not by much. But suddenly, life on The Great Sea becomes a school. Troubles and blessings, whether one's own or another's, are simply lessons to help prepare for what comes next. If so, then why not just say what comes next? Maybe because what comes next is entirely determined by what takes place? It changes things drastically, at least in the minds of some.

Was the High King good or bad? Each reader will make up his/her own mind regarding that, and that is as it should be. Some will express their opinion to others, and that is well and good. Others may even seek to persuade others to believe as they do, which is fine. Some will get angry when others disagree with them. That is unfortunate.

In any case, what is the Author's intent? Well, that would be me. With regard to Swords of Fire, I am the one who has the power to put a stop to anything I choose. Even the High King cannot act apart from my will. As a writer, I make the determination over what is good, what is bad - and what is simply a matter of perspective. When someone reads what I have written, the story becomes their's, and they will make these determinations.

For the record, I believe the High King is good - because he conforms to my idea of goodness. However, even I must concede that he cannot be wholly good, because my idea of goodness tends to be somewhat fluid, changing as I grow in knowledge and experience. It isn't runny, like pure water. It is more like a thick lava crawling across the ground. It will harden in time, but that is not to say a great upheaval cannot change it.

So it is with me. Many of my beliefs regarding good and bad have hardened. Not all. New experience still affects my views on many things, and in some things I have completely reversed my thinking over the years. This is especially so in areas involving punishment and forgiveness. I don't see far, but I see further ahead than I did before. My physical eyes continue to weaken, but my inner eyes, my comprehension, increase, albeit slowly. As I understand better, I can see further ahead - to a point. This is affecting how I view good and bad and punishment and forgiveness. I see myself differently, and so I see others differently. I don't always like what I see in me, but I'm realizing I am so much like everyone else - even if I am so different.

Is the High King good? Of course he is, silly. He is me. How can I see him any other way?

Some would hold that, since the High King has the power to stop all evil but doesn't, the High King is himself evil. They maintain that a good being of such power would suppress all evil and keep The Great Sea at peace. But there is a problem with that which the Evil Viewers (those who see the High King as evil, not viewers who are evil) refuse to acknowledge. In order to suppress all evil, the High King (or whoever) would have to suppress all freedom, because the simple truth is - everyone tends to evil. The Evil Viewers deny this, but it is true. All beings, creatures and what have you are inclined to act out of selfish motive. Not only that, but what one being, creature or what have you considers evil, another might consider their 'right', and to be denied that right is evil. You see, it comes down to how one defines evil. Let us look at The Great Sea.

The High King created The Great Sea. It was his to give to whomever he chose. He gave it to the Children of Fire, but with the understanding it was eventually to go to Madatar and Ardora. Until Madatar and Ardora claimed their gift, Kensington was to rule and Draem and Zenophone were to support him. Fair enough.

But in Zenophone's mind, he was far better suited to rule the Sea than Kensington. Furthermore, why should the Sea be given to Madatar and Ardora when they had no part in fashioning it? After all, was it not the Children who did most of the actual work? In Zenophone's mind, it was evil for him to do all of that work and get nothing in reward. It wasn't fair that Madatar and Ardora should be given something for which they had not labored. Evil.

From Kensington's point of view it did not matter that Madatar had not been present. The Sea belonged to the High King and the High King was free to give it to whomever he wished. It could be argued that being given the regency may have influenced Kensington's thinking. Would he have thought the same had Zenophone been chosen as regent? In any case, from Kensington's point of view, refusal to abide by the High King's decision was evil.

But it goes even further than that. The concept of what is evil and what is good filters down into the very basic elements which make up life on the Sea. The mortal beings who have been given free thought - and thus named Free People - have dominion over the creatures which live out their existence by instinct. Horses, sheep, cattle and other creatures are forced to serve Men, Dwarfs and Figgits. Is that fair? What is more, some creatures live by feeding upon others. Is that fair? Some say yes and some say no.

The High King set the rules by allowing certain things to be and not others. Individual concepts of his goodness - or lack of it - derive from a selfish perspective. The free thinking beings considered actions which supported their wants and desires to be good, and those which interfered with them bad. Beasts and other creatures didn't care one way or another. They just lived until they died, and perhaps that is the pivitol point on which good and evil truly separate. There is life, and then there is death. What happens after death? Nothing? Transition? Eternity? What happens?

If, as some claimed, death was the end of whatever/whoever died, then life on The Great Sea was all important, and whatever happened on The Great Sea was all important. So to be denied a good life for no apparent reason was evil.

But what if there was more? What if life on The Great Sea was akin to living in a nursery? What if dying simply meant graduation? That changes things a bit, although there are those who would say not by much. But suddenly, life on The Great Sea becomes a school. Troubles and blessings, whether one's own or another's, are simply lessons to help prepare for what comes next. If so, then why not just say what comes next? Maybe because what comes next is entirely determined by what takes place? It changes things drastically, at least in the minds of some.

Was the High King good or bad? Each reader will make up his/her own mind regarding that, and that is as it should be. Some will express their opinion to others, and that is well and good. Others may even seek to persuade others to believe as they do, which is fine. Some will get angry when others disagree with them. That is unfortunate.

In any case, what is the Author's intent? Well, that would be me. With regard to Swords of Fire, I am the one who has the power to put a stop to anything I choose. Even the High King cannot act apart from my will. As a writer, I make the determination over what is good, what is bad - and what is simply a matter of perspective. When someone reads what I have written, the story becomes their's, and they will make these determinations.

For the record, I believe the High King is good - because he conforms to my idea of goodness. However, even I must concede that he cannot be wholly good, because my idea of goodness tends to be somewhat fluid, changing as I grow in knowledge and experience. It isn't runny, like pure water. It is more like a thick lava crawling across the ground. It will harden in time, but that is not to say a great upheaval cannot change it.

So it is with me. Many of my beliefs regarding good and bad have hardened. Not all. New experience still affects my views on many things, and in some things I have completely reversed my thinking over the years. This is especially so in areas involving punishment and forgiveness. I don't see far, but I see further ahead than I did before. My physical eyes continue to weaken, but my inner eyes, my comprehension, increase, albeit slowly. As I understand better, I can see further ahead - to a point. This is affecting how I view good and bad and punishment and forgiveness. I see myself differently, and so I see others differently. I don't always like what I see in me, but I'm realizing I am so much like everyone else - even if I am so different.

Is the High King good? Of course he is, silly. He is me. How can I see him any other way?

Friday, December 12, 2008

The Worlds and Their Origins

When the High King created The Great Sea he did not do all of the work himself. He could have, but that is not the way he does things. Instead, he provided the direction and means and allowed the Children of Fire to build it. The King did make the original foundation, and the Fire which sustained the Sea was his. But the actual fashioning was done by the Children of Fire. Think of it as a Master Craftsman handing his students a basic form, such as a ball of clay, and telling them to reshape it into a bird, or a tree, or anything. That is what the High King did.

Some place in the archives (I can't find it now) I have an account of how the first world was created. It was Kensington who made it. He, Draem and Zenophone had just arrived. The Fire in the midst of the ring had already melted much of the ice, and the High King had blown upon the waters to start the rotation. Kensington stepped upon the Sea, and when he lifted his foot, land from beneath the surface, broke free and rose. The three Lords walked the Sea, breaking up more and more pieces of land, and generating a thick steamy cloud in the process. Soon, they were joined by others, and the footprints of their frolicking became the worlds.

The Children watched the worlds (lifeless pieces of earth) race across the waters, crashing, merging and sinking. Eventually, they began pushing the worlds together, creating a massive piece of land which became a vortex to everything else. It was upon this Original World that the High King introduced Life. It was an explosion of life. The waters had life. The land had life. There was life in the air. And the Children were allowed to tend and direct this life, as gardeners and herdsmen.

The Children governed their new world from its center. For time uncounted this continued. Then, at last, Zenophone believed he was ready and made his move to take sole control. And so began The Great War. But Zenophone had miscalculated. His followers did not number so highly as he had deceived himself into believing. Neither did all of the creatures he had made come to him. Only a few dragons took his side, and none of the most powerful. Unwilling to relent, Zenophone chose to see the Great Sea destroyed rather than allow another to have it.

The World was rent apart, killing great numbers of the Sea's life. But before all was lost the High King intervened. Like a parent putting a stop to a fight between siblings which has escalated to a point of danger, the High King ended the War and imposed restrictions on what the Children could, and could not, do henceforth. All who had participated were confined to the Sea, even those who's strength had been exhausted. For them, two isles were made: The Isle of Wonder, for those who had fought beside Kensington and Draem; and The Isle of Nether Gloom, for those who had fought with Zenophone.

The King gave them their decree. "The isles shall beckon to you according to your deeds. When your strength gives way you shall be pulled directly to the isle which holds your heart. From the Isle of Nether Gloom there is no escape. Those who go there will remain in their confinement until I at last put an end to the Sea. On the Isle of Wonder you will rest and regain your strength. When you are able, you will be free to rejoin in the work of repair."

The Children were then tasked with repairing the Sea, in as much as it could be repaired. They were forbidden to rejoin the pieces of their world because the upheaval required would kill the life which remained. So the worlds were left separate. They were hidden from each other by the cloud of mist which still hung over the waters. Each moved over the waters at its own pace, and each had it's own time. The Children built portals, windows from one world to another to allow quick passage. In time, there was a new routine.

But Zenophone was not content. The Sea had been promised to Madatar. What, he thought, if Madatar was not able to claim his prize? What if he were to be so decimated that he was trapped on one of the isles? And so Zenophone, and all who were too proud to return to Kensington, set about to find Madatar and destroy him. It was a dangerous game they played. Madatar was stronger than any one of them, including Zenophone. And should he join with Ardora, there would be no chance of victory. They were limited in what they could do. If they pushed too hard, the High King might intervene again. But for whatever his reasons, the High King was not interfering at the moment. The race was on. Madatar was somewhere on The Great Sea. But on which world?

Some place in the archives (I can't find it now) I have an account of how the first world was created. It was Kensington who made it. He, Draem and Zenophone had just arrived. The Fire in the midst of the ring had already melted much of the ice, and the High King had blown upon the waters to start the rotation. Kensington stepped upon the Sea, and when he lifted his foot, land from beneath the surface, broke free and rose. The three Lords walked the Sea, breaking up more and more pieces of land, and generating a thick steamy cloud in the process. Soon, they were joined by others, and the footprints of their frolicking became the worlds.

The Children watched the worlds (lifeless pieces of earth) race across the waters, crashing, merging and sinking. Eventually, they began pushing the worlds together, creating a massive piece of land which became a vortex to everything else. It was upon this Original World that the High King introduced Life. It was an explosion of life. The waters had life. The land had life. There was life in the air. And the Children were allowed to tend and direct this life, as gardeners and herdsmen.

The Children governed their new world from its center. For time uncounted this continued. Then, at last, Zenophone believed he was ready and made his move to take sole control. And so began The Great War. But Zenophone had miscalculated. His followers did not number so highly as he had deceived himself into believing. Neither did all of the creatures he had made come to him. Only a few dragons took his side, and none of the most powerful. Unwilling to relent, Zenophone chose to see the Great Sea destroyed rather than allow another to have it.

The World was rent apart, killing great numbers of the Sea's life. But before all was lost the High King intervened. Like a parent putting a stop to a fight between siblings which has escalated to a point of danger, the High King ended the War and imposed restrictions on what the Children could, and could not, do henceforth. All who had participated were confined to the Sea, even those who's strength had been exhausted. For them, two isles were made: The Isle of Wonder, for those who had fought beside Kensington and Draem; and The Isle of Nether Gloom, for those who had fought with Zenophone.

The King gave them their decree. "The isles shall beckon to you according to your deeds. When your strength gives way you shall be pulled directly to the isle which holds your heart. From the Isle of Nether Gloom there is no escape. Those who go there will remain in their confinement until I at last put an end to the Sea. On the Isle of Wonder you will rest and regain your strength. When you are able, you will be free to rejoin in the work of repair."

The Children were then tasked with repairing the Sea, in as much as it could be repaired. They were forbidden to rejoin the pieces of their world because the upheaval required would kill the life which remained. So the worlds were left separate. They were hidden from each other by the cloud of mist which still hung over the waters. Each moved over the waters at its own pace, and each had it's own time. The Children built portals, windows from one world to another to allow quick passage. In time, there was a new routine.

But Zenophone was not content. The Sea had been promised to Madatar. What, he thought, if Madatar was not able to claim his prize? What if he were to be so decimated that he was trapped on one of the isles? And so Zenophone, and all who were too proud to return to Kensington, set about to find Madatar and destroy him. It was a dangerous game they played. Madatar was stronger than any one of them, including Zenophone. And should he join with Ardora, there would be no chance of victory. They were limited in what they could do. If they pushed too hard, the High King might intervene again. But for whatever his reasons, the High King was not interfering at the moment. The race was on. Madatar was somewhere on The Great Sea. But on which world?

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Madatar and Ardora

Madatar was part of the original creation - both mine, and the High King's. Who and what he was grew as I continued to write until he became the one for whom the Great Sea was created.

Ardora is a more recent, but logical, creation - mine, NOT the High King's. Ardora began when Madatar began. She is the compliment to Madatar - the Yin to his Yang.

Madatar and Ardora are also beings of Fire. Spirits, if you will, but of a different order than the other Children of Fire. Individually, they became more powerful than any other on the Great Sea, save the High King himself. Collectively, they became more powerful than everyone, and everything, combined on the Great Sea, save the High King. But they are not together.

Shortly after the Great Sea's creation, Zenophone and his followers attempted to take the Great Sea for their own. Ultimately this resulted in the Great War, in which the Sea itself was nearly destroyed. It was at this time Madatar and Ardora were separated and hid from each other. For while they were destined to become the reigning power over the Great Sea, they had yet to achieve that stature. In the early days of the Sea's history they were vulnerable. So the High King hid them, and not even Kensington knew where.

Why would the High King separate them? It is not always easy to know the thoughts of the High King. But this we know: Even at the Beginning, Madatar nor Ardora did not have the power to defeat Zenophone and his followers. However, together their growth would cause ripples across the Sea which would only draw their enemies to them. Separated, the ripples became confused with all else that was taking place.

That is the story of Swords of Fire. It is the saga of Madatar and Ardora's search for each other and their ultimate battle with Zenophone and his followers. It is presented from the perspective of one Khirsha, son of Klarissa and Shello, of the Line of Swords, in the House of Jora. Khirsha became the eye of the storm, so to speak.

Ardora is a more recent, but logical, creation - mine, NOT the High King's. Ardora began when Madatar began. She is the compliment to Madatar - the Yin to his Yang.

Madatar and Ardora are also beings of Fire. Spirits, if you will, but of a different order than the other Children of Fire. Individually, they became more powerful than any other on the Great Sea, save the High King himself. Collectively, they became more powerful than everyone, and everything, combined on the Great Sea, save the High King. But they are not together.

Shortly after the Great Sea's creation, Zenophone and his followers attempted to take the Great Sea for their own. Ultimately this resulted in the Great War, in which the Sea itself was nearly destroyed. It was at this time Madatar and Ardora were separated and hid from each other. For while they were destined to become the reigning power over the Great Sea, they had yet to achieve that stature. In the early days of the Sea's history they were vulnerable. So the High King hid them, and not even Kensington knew where.

Why would the High King separate them? It is not always easy to know the thoughts of the High King. But this we know: Even at the Beginning, Madatar nor Ardora did not have the power to defeat Zenophone and his followers. However, together their growth would cause ripples across the Sea which would only draw their enemies to them. Separated, the ripples became confused with all else that was taking place.

That is the story of Swords of Fire. It is the saga of Madatar and Ardora's search for each other and their ultimate battle with Zenophone and his followers. It is presented from the perspective of one Khirsha, son of Klarissa and Shello, of the Line of Swords, in the House of Jora. Khirsha became the eye of the storm, so to speak.

Posted by

Bevie

at

1:48 AM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

High King,

Madatar-Ardora,

Saga Elements

Monday, December 8, 2008

Lord Kensington

Kensington was the "chief" of all the Children of Fire who came to the Great Sea. My original thought was that Kensington was to rule the Sea but, as I stated in the previous post, that quickly changed.

In Flames of Hatred, Shatahar's servant, Vitchkl, makes a reference to Kensington's Pillar. The meaning of this odd statement is not given in Flames of Hatred, although I suspect attentive readers are able to figure it out through context. I will spell it out plainly: Kensington's Pillar is Fire Mountain, the place where the family gets the ore to create flameswords. In fact, the ore's power is Kensington's power. There is more to it, but that is essentially it.

Kensington created the pillars as nesting pods for the Phoenix, which he also created. The Phoenix had the power of healing, but they were weakened in doling it out. The pillars allowed them to renew their strength quickly, although that was not the Phoenix's sole source of renewal. All creatures took renewal from the Fire which was at the Sea's midst. They called it the sun, but it was much more than that.

Not all worlds had a pillar, and at the time of Flames of Hatred the Phoenix are considered mythological because few, if any, survived the Great War which nearly destroyed the Sea.

Kensington was in command of The Cloud, the mystical place between worlds in which Time had little or no power. He also was in charge of monitoring and moving the Regulator of Time, which was the real age of the Sea. He was in charge of it, but he only moved it at the High King's command.

Neither the Cloud nor the Regulator of Time come into play in Flames of Hatred. The Cloud is seen for the first time in Book II, The Prophecies of Madatar, and the Regulator of Time is referenced in Book III, Bonds of Love. I believe it is Book III in which we get to meet Lord Kensington.

In Flames of Hatred, Shatahar's servant, Vitchkl, makes a reference to Kensington's Pillar. The meaning of this odd statement is not given in Flames of Hatred, although I suspect attentive readers are able to figure it out through context. I will spell it out plainly: Kensington's Pillar is Fire Mountain, the place where the family gets the ore to create flameswords. In fact, the ore's power is Kensington's power. There is more to it, but that is essentially it.

Kensington created the pillars as nesting pods for the Phoenix, which he also created. The Phoenix had the power of healing, but they were weakened in doling it out. The pillars allowed them to renew their strength quickly, although that was not the Phoenix's sole source of renewal. All creatures took renewal from the Fire which was at the Sea's midst. They called it the sun, but it was much more than that.

Not all worlds had a pillar, and at the time of Flames of Hatred the Phoenix are considered mythological because few, if any, survived the Great War which nearly destroyed the Sea.

Kensington was in command of The Cloud, the mystical place between worlds in which Time had little or no power. He also was in charge of monitoring and moving the Regulator of Time, which was the real age of the Sea. He was in charge of it, but he only moved it at the High King's command.

Neither the Cloud nor the Regulator of Time come into play in Flames of Hatred. The Cloud is seen for the first time in Book II, The Prophecies of Madatar, and the Regulator of Time is referenced in Book III, Bonds of Love. I believe it is Book III in which we get to meet Lord Kensington.

Posted by

Bevie

at

5:37 PM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

High King,

Mythological Creatures,

Phoenix

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

The High King

The High King is the Great Sea's Creator. It is generally accepted to reference the High King as male, but in actuality the High King is a spirit, and so without gender.

The High King does not enter directly into any of the existing novels, although reference is made to him in a variety of ways. As of this posting, I can think of only one instance in which the High King speaks directly to anyone, and that is in a book which has yet to be written, so it may not even happen.

Although vocally absent, the sense remains that the High King is still very interested in what transpires in and on the Great Sea. Certainly he has the power to intervene however he wishes. It is to be assumed that he does, but that his methods of intervention are so intertwined with the natural course of events on the Great Sea it is difficult, if not impossible, to know when something took place by reason of intervention or simply as a matter of course.

This 'detachment', as it were, is necessary to the presentation of Swords of Fire. The characters who struggle through their lives must be seen to resolve their conflicts through natural means. No 'miracles' will aid them. (At least, none which are not of their own devising.) But as stated earlier, the High King is very interested in what transpires in and on the Great Sea.

The High King does not enter directly into any of the existing novels, although reference is made to him in a variety of ways. As of this posting, I can think of only one instance in which the High King speaks directly to anyone, and that is in a book which has yet to be written, so it may not even happen.

Although vocally absent, the sense remains that the High King is still very interested in what transpires in and on the Great Sea. Certainly he has the power to intervene however he wishes. It is to be assumed that he does, but that his methods of intervention are so intertwined with the natural course of events on the Great Sea it is difficult, if not impossible, to know when something took place by reason of intervention or simply as a matter of course.

This 'detachment', as it were, is necessary to the presentation of Swords of Fire. The characters who struggle through their lives must be seen to resolve their conflicts through natural means. No 'miracles' will aid them. (At least, none which are not of their own devising.) But as stated earlier, the High King is very interested in what transpires in and on the Great Sea.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Today's Music

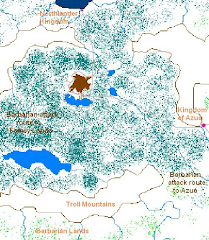

Yeah. That's The Great Sea all right.