In Book II we learn quite a bit about the Ceres and Elves. It probably isn't fair to make a post based on the second book in a series for which the first has yet to be published (and therefore is unavailable). However, what you will find is that the culture of the Ceres and Elves in Book II has a great many similarities to Khirsha's family culture. There are also some significant differences, which produces the comic thread in Book II.

I will try to keep this post focused on the topic listed in the title, but if you've been reading me at all you know I tend to wander about.

Although few human societies were gender equal, for the other four races 'equality' was common. Males and females had their basic roles, but the ability to branch from these was easy - providing cultural requirements were met. But for Figgits, Dwarfs, Pennans and Nomads, gender was not an exclusionary factor. In those four races we find ability and interest played a much bigger role in deciding one's role in their society. There were exceptions. Every society has its own quirks and prejudices which seem normal to it, but quite odd to others which do not share the quirk. So, since the Elves were the product of a Pennan and a Nomad, their society followed the same path.

Regarding marriage, courting and other things of that nature, the four 'equal' races chose practicality as their judgment rod. What does this mean? Well, like most cultures, the perpetuation of the culture was of foremost concern. This meant taking care of the citizens, or at least making sure the citizens were well able to take care of themselves. The ability to grow, or trade for, the things living required (food, clothing, shelter) was the primary factor. What about children? Well, depending on the society, children were able/required to work based on their age. They were the responsibility - not the possession - of their parents. This point is key, for it drove the decision on who would hold the final say in family matters.

Although each society had its own methods to attempt birth control, their effectiveness varied from 'why bother' to 'most of the time'. Only a very few cultures managed to find the 'most of the time' method, and that usually by luck. (Khirsha's family was one of those, and it was due mostly to luck - but whether good or bad is hard to tell. The Power of the ore in Fire Mountain leeched into the land and water and infected all living things within its range. One side-effect - for Khirsha's family anyway - was a reduction in birth rate.) This meant that females desiring a more - copulatory - relationship with a male ran the risk of becomming pregnant. Should this happen, they could not escape it. The pregnancy would be with them until the child/children were born. Males did not have this problem. They could leave, claiming they had nothing to do with the creation of this new offspring. It would be their word against the females. How was this to be resolved?

The answer became easy. Not wanting to have 'orphaned' children in large numbers, these societies (Nomads, Pennans, Dwarfs and Figgits) decided the female's voice would be heard - and no other. Now, there was no 'her word versus his word' scenarios. It was the female's word. And in virtually all of these societies, the consequence of creating a child was instant betrothal to the co-defendant.

So. Question. Does this mean that a woman, Nonkanta (not desired), could give herself to a man, Kert (simpleton), become pregnant, and then claim that Sohan (charming, handsome) was the father? (source of names: http://www.babynames.com/Names/search.php)

Yes.

It happened, but not nearly so much as imagination would allow. Generally, if a woman (young or otherwise) was willing to engage in this behavior it was because the male she had chosen to do it with was the male she had chosen. If there was any deception involved, it was in convincing the male to participate - but what kind of deception does a woman need for that?

Nonkanta: Hey, Sohan! Do you want to have sex with me?

Sohan: You bet! Let's do it!

For this reason, it was decreed the females would decide who they wanted to court, and the males would have to wait to be asked. The (absolutely correct) thinking was that the males would respond to overtures from virtually any female, whereas females were more selective in choosing mates. So the females got to choose.

One practice of the Ceres and Elves not practiced by Khirhsa's family was the concept of multiple spouses. It wasn't completely straightforward, however. In fact, the rules surrounding it could be quite convoluted - to an outsider. It made perfect sense to them.

In Cere and Elvish culture, having more than one husband, or more than one wife, was acceptable - if one belonged to a Royal House. And this is where the convolutions begin. Royal House membership was not necessarily lifelong, and it was possible to become Royal House through no effort. So what was a Royal House?

Simply put, belonging to a Royal House meant one could trace their lineage back to one of the current advisors to the king/queen, or to the king/queen or their spouse/s. Kings and Queens sometimes 'fired' advisors, replacing them with new members. But while one belonged to a Royal House, one had the right to pursue and acquire multiple partners. This included pursuing partners who were already married. Some of the social relationships were quite messy.

The number of Royal Houses at any given time was dependent on the population. Small populations meant for few Royal Houses while large populations meant the reverse.

Adding to the mess was the fact that one did not have to actually belong to a Royal House in order to participate in this benefit. Only one partner needed to belong to a Royal House. So, Royal House women could seek out males who were not Royal House. Further, non-Royal House women could seek out males who were. Remember, males could not seek out anyone. However, they could - within protocol - make it known to the females that they were available to court. This was done in a variety of ways, depending on the specific society. It is also what gets Khirsha into trouble in Book II.

So what happened to the extended households when Royal House status was removed? Nothing. No marriage could be annulled. Once it existed, it existed.

One last point on marriages. Excepting the case of marriage by pregnancy, all marriages had to be approved, generally by parents. In the case of multiple spouses, the spouses had to approve.

Example:

Woman1 is married to Man1.

Woman2 is married to Man2.

Woman3 is not married.

Man3 is not married.

Woman1 wants to make Man3 her Second Husband.

Man1 must approve.

Man3's parents must approve.

Woman2 wants to make Man1 her Second Husband.

Man2 must approve.

Woman1 must approve. (approval was given far more often than you might think)

Woman3 wants to make Man3 her First Husband, and Man2 her Second Husband.

Man3's parents must approve.

Woman2 must approve.

Convoluted? Messy? What about the children? Wouldnt' that be a mess when it came time for them to find partners?

Yes. It was a mess. But each society's members had no trouble keeping things in order.

The final approval required (except in cases of pregnancy) was the new couple's ability to provide for any/all projected children.

The marriage institution for Ceres and Elves was like a giant entanglement. This is the culture Khirsha is thrown into in Book II. His method for surviving within it is interesting.

Showing posts with label Culture. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Culture. Show all posts

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Saturday, December 27, 2008

Tavaar - 2nd Edition

Yes, I am back to talking about Tavaar. I think she is probably the most interesting of all the characters, but she is not the Main Character. Why not, if she is so interesting? There are several reasons, but a lot of it has to do with the fact that she's only had a name for the last ten years. Thirty years ago, at the story's conception, she didn't even exist. She's a Sally-Come-Lately, but a wonderful addition. I think.

Last week I left off with Tavaar having lost the annual Mock Sword Tournament to Shello. It was the first time she had ever lost to anyone, and it didn't sit well. Her idiot brother, Pulich, who was eleven years older, torked her off and she fought him. She didn't win - but neither did she lose. An important point. (very important)

We begin this week with Tavaar having won the Mock Sword Tournament at the age of ten. Family members would compete in the Mock Sword Tournament eighteen times, beginning at age eight (8) and completing their run at age twenty-five (25). There were six (6) groupings (NOTE: I am using our lettering. Their alphabet was completely different.):

Group A: 8-year-olds (They competed alone)

Group B: 9 and 10-year-olds (9)

Group C: 11 to 13-year-olds (12, 13)

Group D: 14 to 16-year-olds (14, 15)

Group E: 17 to 20-year-olds (17*, 18, 19)

Group F: 21 to 25-year-olds (21, 22, 23**, 24)

The numbers to the right (without stars) indicate the ages when Tavaar had to compete against Shello, who was a year older than she. She would lose to him every time. When she didn't have to compete against him, she won. At seventeen, Tavaar fought Khaiu, and she fought Klarissa at age twenty-three.

I apologize for the writing. This is pretty much how it was written by hand in a notebook. I've made a few minor changes, but nothing significant. My purpose in these first drafts is to simply get what happened down. I worry less about the how, trusting myself to edit it appropriately later.

The pattern continued. When Tavaar competed against Shello, she lost. Otherwise, she won. Their battles were fierce, and it always seemed she could win, but she never did. She hated the defeats, but she was gaining respect for this warrior who would not be beaten. What she did not know was she was also making a favorable impression on Shello and his older brother, (1)Khaiu. She became aware of it when she won the sword championship at age sixteen. Shello and Khaiu came to congratulate her. They greeted her with kisses, as was the custom. However, when Shello kissed her the kiss became passionate. Tavaar had kissed before, many times. Kissing was actually encouraged at the full moon bonfires. Up to this moment, though, Tavaar had never felt the passion, despite her efforts to generate it. Now, with Shello’s lips pressed against her own, passion awoke, touching every nerve, giving her a new awareness of touch and sensuality.

They broke apart. Tavaar's breathing was shallow, and her entire body felt warm. At first she was enraptured, but that immediately changed to a feeling of being exposed. She looked into his eyes, longing for reassurance but terrified of finding mocking laughter. She had been caught by surprise, which did not happen often. She was afraid. But Shello’s eyes showed no laughter. There was no hint of triumph or accomplishment. He looked startled, perhaps even amazed. And there was something else: Shello looked timid and fearful. He had been caught by surprise, too.

Tavaar recovered her poise and with an exhilarating realization she understood she finally had the advantage of this magnificent young warrior. She took the initiative. She kissed him again. This time the passion was not accidental. She had summoned it. It had come at her desire and he was helpless against it. She had won.

Khaiu broke them apart unceremoniously, remarking that he and Shello still had to fight each other for the seventeen to twenty-year-old championship. Tavaar let them go. Shello’s frequent looks back were all she needed. She wasn't a little girl anymore.

(1) references a footnote which simply states: This was the first hint that Khaiu, not Shello, would be Tavaar’s actual love.

From this point on Tavaar is no longer just a little girl who can fight well. She is now aware of her sexuality, and quickly learns how to use it to her advantage. She is entering that period of her life which will generate her reputation henceforth. Some of it was fun to write. Some of it wasn't.

Book I explicitly states that Tavaar and Shello were once lovers. Now here, in a passage written later, we are told Khaiu was Tavaar's actual love. How do these two seemingly opposing statements reconcile to each other? Simple. Tavaar loved them both, and she took both for lovers. But according to this footnote, she loved Khaiu more.

Now, to something related.

Tavaar was sixteen when she first experienced these feelings of sexuality and desire. In Book I, Khirhsa is nineteen. And if you read through the archives you would find this is about right for everyone in the family - all seven thousand of them.

Seems a bit old, doesn't it? Maybe even - odd?

There are reasons for it, but none of the books directly address any of them. The books treat this as normal and hence have little to say about it. However, since at least one person has remarked unfavorably about this, more than implying there is something "wrong", or even sick about it, I will try to explain.

First, and this is most important, the reader must understand that Swords of Fire does not take place in modern day America, England, France, Germany, Australia, Brazil, Kenya or any other place on this planet. In Western Culture, sexuality comes early (much too early to my way of thinking, but that's a different topic) to our children. Some are dating as young as twelve, including sexual activity. For this reason it is easy for even some of our societies' most conservative members to accept sexual awareness at age sixteen.

One hundred years ago that was far less true than it is today. I do not deny that some pretty wild behavior took place then, but it was far less widespread - and certainly less acceptable. When I was young, living in rural Minnesota, only the most wild (in our area anyway) ever went on dates before sixteen, and most did not date until they were seventeen or older. Television was only beginning to relax its standards, and magazine and billboard advertising were quite tame compared to what we find today.

My point? Even thirty years ago a sixteen-year-old knew a lot less about sex and sexual behavior than sixteen-year-olds today. And in other cultures (we might call them primitive, but they might not appreciate that) this sexual ignorance was even more pronounced. Physical maturity plays a big role in sexual awareness, but Culture can - and often does - suppress it. That is the case in Khirhsa's family. It is a cultural thing, whether we like/agree with it or not.

But beyond culture, there is another overriding force which affected the people in Khirhsa's family. That is the water from Fire Mountain and Fire Lake.

In Book I, the water is spoken of as having healing properties. It heals minor wounds quickly, and cures minor illnesses. The Power of the mountain has leeched into the water, the soil, the food they eat, the animals they hunt and - themselves. It has extended their lifespans by as much as fifty percent. It has made them physically strong. But not all of the effects are desirable. While stronger than any other of the Free People, they mature much more slowly, particularly after the age of twenty. (Tavaar is fifty-six when she and Khirsha have their romantic encounter. Khirsha is nineteen. Converting their physical ages to our own it would be more like twenty-eight and sixteen.) Also, in line with this, they do not reproduce as quickly. A large family would be four children. Most had two or three.

The books do not address these issues directly, beyond hinting that the water explains their lifespans. When entering any new world there are some things which are not explained. One must just accept them as parts of the reality in which one now resides.

Last week I left off with Tavaar having lost the annual Mock Sword Tournament to Shello. It was the first time she had ever lost to anyone, and it didn't sit well. Her idiot brother, Pulich, who was eleven years older, torked her off and she fought him. She didn't win - but neither did she lose. An important point. (very important)

We begin this week with Tavaar having won the Mock Sword Tournament at the age of ten. Family members would compete in the Mock Sword Tournament eighteen times, beginning at age eight (8) and completing their run at age twenty-five (25). There were six (6) groupings (NOTE: I am using our lettering. Their alphabet was completely different.):

Group A: 8-year-olds (They competed alone)

Group B: 9 and 10-year-olds (9)

Group C: 11 to 13-year-olds (12, 13)

Group D: 14 to 16-year-olds (14, 15)

Group E: 17 to 20-year-olds (17*, 18, 19)

Group F: 21 to 25-year-olds (21, 22, 23**, 24)

The numbers to the right (without stars) indicate the ages when Tavaar had to compete against Shello, who was a year older than she. She would lose to him every time. When she didn't have to compete against him, she won. At seventeen, Tavaar fought Khaiu, and she fought Klarissa at age twenty-three.

I apologize for the writing. This is pretty much how it was written by hand in a notebook. I've made a few minor changes, but nothing significant. My purpose in these first drafts is to simply get what happened down. I worry less about the how, trusting myself to edit it appropriately later.

The pattern continued. When Tavaar competed against Shello, she lost. Otherwise, she won. Their battles were fierce, and it always seemed she could win, but she never did. She hated the defeats, but she was gaining respect for this warrior who would not be beaten. What she did not know was she was also making a favorable impression on Shello and his older brother, (1)Khaiu. She became aware of it when she won the sword championship at age sixteen. Shello and Khaiu came to congratulate her. They greeted her with kisses, as was the custom. However, when Shello kissed her the kiss became passionate. Tavaar had kissed before, many times. Kissing was actually encouraged at the full moon bonfires. Up to this moment, though, Tavaar had never felt the passion, despite her efforts to generate it. Now, with Shello’s lips pressed against her own, passion awoke, touching every nerve, giving her a new awareness of touch and sensuality.

They broke apart. Tavaar's breathing was shallow, and her entire body felt warm. At first she was enraptured, but that immediately changed to a feeling of being exposed. She looked into his eyes, longing for reassurance but terrified of finding mocking laughter. She had been caught by surprise, which did not happen often. She was afraid. But Shello’s eyes showed no laughter. There was no hint of triumph or accomplishment. He looked startled, perhaps even amazed. And there was something else: Shello looked timid and fearful. He had been caught by surprise, too.

Tavaar recovered her poise and with an exhilarating realization she understood she finally had the advantage of this magnificent young warrior. She took the initiative. She kissed him again. This time the passion was not accidental. She had summoned it. It had come at her desire and he was helpless against it. She had won.

Khaiu broke them apart unceremoniously, remarking that he and Shello still had to fight each other for the seventeen to twenty-year-old championship. Tavaar let them go. Shello’s frequent looks back were all she needed. She wasn't a little girl anymore.

(1) references a footnote which simply states: This was the first hint that Khaiu, not Shello, would be Tavaar’s actual love.

From this point on Tavaar is no longer just a little girl who can fight well. She is now aware of her sexuality, and quickly learns how to use it to her advantage. She is entering that period of her life which will generate her reputation henceforth. Some of it was fun to write. Some of it wasn't.

Book I explicitly states that Tavaar and Shello were once lovers. Now here, in a passage written later, we are told Khaiu was Tavaar's actual love. How do these two seemingly opposing statements reconcile to each other? Simple. Tavaar loved them both, and she took both for lovers. But according to this footnote, she loved Khaiu more.

Now, to something related.

Tavaar was sixteen when she first experienced these feelings of sexuality and desire. In Book I, Khirhsa is nineteen. And if you read through the archives you would find this is about right for everyone in the family - all seven thousand of them.

Seems a bit old, doesn't it? Maybe even - odd?

There are reasons for it, but none of the books directly address any of them. The books treat this as normal and hence have little to say about it. However, since at least one person has remarked unfavorably about this, more than implying there is something "wrong", or even sick about it, I will try to explain.

First, and this is most important, the reader must understand that Swords of Fire does not take place in modern day America, England, France, Germany, Australia, Brazil, Kenya or any other place on this planet. In Western Culture, sexuality comes early (much too early to my way of thinking, but that's a different topic) to our children. Some are dating as young as twelve, including sexual activity. For this reason it is easy for even some of our societies' most conservative members to accept sexual awareness at age sixteen.

One hundred years ago that was far less true than it is today. I do not deny that some pretty wild behavior took place then, but it was far less widespread - and certainly less acceptable. When I was young, living in rural Minnesota, only the most wild (in our area anyway) ever went on dates before sixteen, and most did not date until they were seventeen or older. Television was only beginning to relax its standards, and magazine and billboard advertising were quite tame compared to what we find today.

My point? Even thirty years ago a sixteen-year-old knew a lot less about sex and sexual behavior than sixteen-year-olds today. And in other cultures (we might call them primitive, but they might not appreciate that) this sexual ignorance was even more pronounced. Physical maturity plays a big role in sexual awareness, but Culture can - and often does - suppress it. That is the case in Khirhsa's family. It is a cultural thing, whether we like/agree with it or not.

But beyond culture, there is another overriding force which affected the people in Khirhsa's family. That is the water from Fire Mountain and Fire Lake.

In Book I, the water is spoken of as having healing properties. It heals minor wounds quickly, and cures minor illnesses. The Power of the mountain has leeched into the water, the soil, the food they eat, the animals they hunt and - themselves. It has extended their lifespans by as much as fifty percent. It has made them physically strong. But not all of the effects are desirable. While stronger than any other of the Free People, they mature much more slowly, particularly after the age of twenty. (Tavaar is fifty-six when she and Khirsha have their romantic encounter. Khirsha is nineteen. Converting their physical ages to our own it would be more like twenty-eight and sixteen.) Also, in line with this, they do not reproduce as quickly. A large family would be four children. Most had two or three.

The books do not address these issues directly, beyond hinting that the water explains their lifespans. When entering any new world there are some things which are not explained. One must just accept them as parts of the reality in which one now resides.

Sunday, December 21, 2008

So What is the 'Religious' Message

There isn't one. Not officially. However, I remember giving the book to a co-worker a few years back. She liked to read fantasy, and she was very intelligent, so when she expressed an interest in reading what I had written I told her I would be pleased to hear what she had to say about it.

She only came back with two comments. The first was I had a tendency to shift the Point of View (POV). I thought I had corrected that, but I even got called on it from the Minions when I submitted my first 300 words to Evil Editor (http://evileditor.blogspot.com). The second was that it was "too religious" for her to get into. I argued that it wasn't relgious at all, but she wouldn't accept it.

I felt bad because she wasn't going to read it again or give me any more help, but I wasn't going to change the story just because she thought it was religious. For one thing, I still didn't think it was. I certainly had no conscious intent, anyway.

Afterward, I tried to figure out why she thought the book was religous. (She didn't want to talk about it.) My only conclusions - right or wrong, I'll never know - were my references to the High King, and that The Great Sea as a created place (suggesting God). Oh, and I supposed she thought Zenophone was Satan. I don't know who she thought was Jesus Christ. There is no Christ figure in the book. None of my characters are without fault, much less sinless. Characters may sacrifice themselves for other characters, but that is true on both sides of the fight. The Barbarians are as likely to sacrifice themselves for their comrades as anyone in Khirsha's family. The point of the book is not about getting to heaven, or being reconciled with the High King. It is about the struggle for control of a place, called The Great Sea. To me, it's not religous.

I think the problem was that Jenni didn't like it that 'religion' was against some things which were part of her lifestyle, and so she was ever alert to defend herself against charges of sin. I didn't put any of that in the book. The book isn't about telling people what's right and what's wrong, or what they should think or believe. When I was young I tried to write like that, but all of that writing was contrived crap. As I have aged I have come to realize nobody has charged me with the task of making anyone believe anything. Those are not the gifts I was given at birth. What I am good at, and what I enjoy doing, is telling stories. That's what Swords of Fire is: a story. And I want the characters to seem real, so every character has both admirable - and not so admirable - traits.

Swords of Fire is not some kind of cheap instruction manual on morality. (You won't get through Book I before you realize my main characters are far from being Champions of Morality.) It is history. It is what happened at a place called, The Great Sea. No brow beating intended. I promise. But I couldn't make Jenni understand that.

All the same, I now believe I was wrong to argue with Jenni about what she got from my book. It is my feeling that when a reader reads a story, it becomes theirs, and they are a free to take from it whatever they wish. I denied Jenni that right, and maybe that's more why she was finished with the book. We were still friends. We talked and laughed about other things, confiding what co-workers confide. But we couldn't talk about the book anymore.

That I have 'religious' (I hate that word) convictions is no surprise. Most people have them. Even believing there is no God is a religious conviction, I think. And I guess it is only a matter of course that what I believe works its way into what I write - particularly as regards fiction. My concepts of good and bad show in some of the family laws/edicts. Most of what I believe to be 'good' and most of what I believe to be 'bad' is shared by most of the people who share my culture. In Swords of Fire, even the so-called 'good' cultures adhere to rules and behavior I do not consider good in my own culture. The same is true for bad. So either I'm a hyprocrite, or I'm not so solid in my convictions as I believe, or it doesn't matter at all because Swords of Fire is just a story. It's a safe exploration of other ways of thinking. I don't know. I think that's too deep for me.

So here's the short answer: Swords of Fire is a story. Take from it what you will. I do hope you enjoy it. That, I did intend.

She only came back with two comments. The first was I had a tendency to shift the Point of View (POV). I thought I had corrected that, but I even got called on it from the Minions when I submitted my first 300 words to Evil Editor (http://evileditor.blogspot.com). The second was that it was "too religious" for her to get into. I argued that it wasn't relgious at all, but she wouldn't accept it.

I felt bad because she wasn't going to read it again or give me any more help, but I wasn't going to change the story just because she thought it was religious. For one thing, I still didn't think it was. I certainly had no conscious intent, anyway.

Afterward, I tried to figure out why she thought the book was religous. (She didn't want to talk about it.) My only conclusions - right or wrong, I'll never know - were my references to the High King, and that The Great Sea as a created place (suggesting God). Oh, and I supposed she thought Zenophone was Satan. I don't know who she thought was Jesus Christ. There is no Christ figure in the book. None of my characters are without fault, much less sinless. Characters may sacrifice themselves for other characters, but that is true on both sides of the fight. The Barbarians are as likely to sacrifice themselves for their comrades as anyone in Khirsha's family. The point of the book is not about getting to heaven, or being reconciled with the High King. It is about the struggle for control of a place, called The Great Sea. To me, it's not religous.

I think the problem was that Jenni didn't like it that 'religion' was against some things which were part of her lifestyle, and so she was ever alert to defend herself against charges of sin. I didn't put any of that in the book. The book isn't about telling people what's right and what's wrong, or what they should think or believe. When I was young I tried to write like that, but all of that writing was contrived crap. As I have aged I have come to realize nobody has charged me with the task of making anyone believe anything. Those are not the gifts I was given at birth. What I am good at, and what I enjoy doing, is telling stories. That's what Swords of Fire is: a story. And I want the characters to seem real, so every character has both admirable - and not so admirable - traits.

Swords of Fire is not some kind of cheap instruction manual on morality. (You won't get through Book I before you realize my main characters are far from being Champions of Morality.) It is history. It is what happened at a place called, The Great Sea. No brow beating intended. I promise. But I couldn't make Jenni understand that.

All the same, I now believe I was wrong to argue with Jenni about what she got from my book. It is my feeling that when a reader reads a story, it becomes theirs, and they are a free to take from it whatever they wish. I denied Jenni that right, and maybe that's more why she was finished with the book. We were still friends. We talked and laughed about other things, confiding what co-workers confide. But we couldn't talk about the book anymore.

That I have 'religious' (I hate that word) convictions is no surprise. Most people have them. Even believing there is no God is a religious conviction, I think. And I guess it is only a matter of course that what I believe works its way into what I write - particularly as regards fiction. My concepts of good and bad show in some of the family laws/edicts. Most of what I believe to be 'good' and most of what I believe to be 'bad' is shared by most of the people who share my culture. In Swords of Fire, even the so-called 'good' cultures adhere to rules and behavior I do not consider good in my own culture. The same is true for bad. So either I'm a hyprocrite, or I'm not so solid in my convictions as I believe, or it doesn't matter at all because Swords of Fire is just a story. It's a safe exploration of other ways of thinking. I don't know. I think that's too deep for me.

So here's the short answer: Swords of Fire is a story. Take from it what you will. I do hope you enjoy it. That, I did intend.

Posted by

Bevie

at

6:37 AM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

Culture,

High King,

Khirsha and His Family

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

The Great Sea's Technologies

I thought I would write a bit about how the Free People do various tasks. All of the civilizations (and there are thousands of them) were primitive by our standards. No one had harnessed electricity. There were no combustion engines. But some were more advanced than others.

Khirsha's family had what I consider to be an odd assortment of technology. On the one hand, they could make swords which burned with fire, and were able to drain power from another sword. Seems like advanced stuff to me. On the other hand, their 'clocks' were almost comical.

The clocks were hourglasses of varying size. The smallest lasted about a minute. The largest went as long as two hours. They were filled with water and manually operated, meaning someone had to be there to turn them when their time ran out. Clearly, this was not an efficient means of keeping time, which suggests something else that is obvious: the family wasn't overly concerned about time of day.

The family did not measure time by minutes and hours. Instead, they measured it in turns and short-turns. (When a glass's top portion emptied, it had to be 'turned'.)

A short-turn lasted roughly one minute. These glasses were used to time events of short duration. During the Presider Flamesword Test in Book I, ten small bottles were used to time each test.

A full-turn, or turn, was about an hour, or sixty short-turns. These glasses were used for meetings, classes and as part of the Village Timekeepers. The Timekeepers were made of twelve full-turns. The first four jars would contain blue tinted water. The next four would be clear. The last four would have red tinted water. Most of the villages had a Timekeeper. One of the Unaligned (a servant class people who are not especially keen on their status) would be responsible for turning the glasses.

The family had 440 houses (I counted them - and I know who lives in every one - do I live an exciting life, or what) in 29 settlements, or villages, but not all had a Timekeeper. Only the eighteen largest villages kept one, and very few houses had one. Some of the family Sovereigns, or other weathy members with live-in servants had them.

The large-turn glasses were only used at the temple during classroom instruction.

Regarding timekeeping, the family was far behind other cultures. Even the nearby Kingdom of Azua had better. But, as I said, time of day was not a significant concern to the family. They were warriors, hunters, farmers and herdsman of cattle. Most gauged their time by the position of the sun. At night, it was the moon - when there was one. Even when things were rushed, their lives were slower than ours.

Khirsha's family had what I consider to be an odd assortment of technology. On the one hand, they could make swords which burned with fire, and were able to drain power from another sword. Seems like advanced stuff to me. On the other hand, their 'clocks' were almost comical.

The clocks were hourglasses of varying size. The smallest lasted about a minute. The largest went as long as two hours. They were filled with water and manually operated, meaning someone had to be there to turn them when their time ran out. Clearly, this was not an efficient means of keeping time, which suggests something else that is obvious: the family wasn't overly concerned about time of day.

The family did not measure time by minutes and hours. Instead, they measured it in turns and short-turns. (When a glass's top portion emptied, it had to be 'turned'.)

A short-turn lasted roughly one minute. These glasses were used to time events of short duration. During the Presider Flamesword Test in Book I, ten small bottles were used to time each test.

A full-turn, or turn, was about an hour, or sixty short-turns. These glasses were used for meetings, classes and as part of the Village Timekeepers. The Timekeepers were made of twelve full-turns. The first four jars would contain blue tinted water. The next four would be clear. The last four would have red tinted water. Most of the villages had a Timekeeper. One of the Unaligned (a servant class people who are not especially keen on their status) would be responsible for turning the glasses.

The family had 440 houses (I counted them - and I know who lives in every one - do I live an exciting life, or what) in 29 settlements, or villages, but not all had a Timekeeper. Only the eighteen largest villages kept one, and very few houses had one. Some of the family Sovereigns, or other weathy members with live-in servants had them.

The large-turn glasses were only used at the temple during classroom instruction.

Regarding timekeeping, the family was far behind other cultures. Even the nearby Kingdom of Azua had better. But, as I said, time of day was not a significant concern to the family. They were warriors, hunters, farmers and herdsman of cattle. Most gauged their time by the position of the sun. At night, it was the moon - when there was one. Even when things were rushed, their lives were slower than ours.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Today's Music

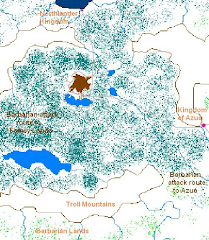

Yeah. That's The Great Sea all right.