I thought I would write a bit about how the Free People do various tasks. All of the civilizations (and there are thousands of them) were primitive by our standards. No one had harnessed electricity. There were no combustion engines. But some were more advanced than others.

Khirsha's family had what I consider to be an odd assortment of technology. On the one hand, they could make swords which burned with fire, and were able to drain power from another sword. Seems like advanced stuff to me. On the other hand, their 'clocks' were almost comical.

The clocks were hourglasses of varying size. The smallest lasted about a minute. The largest went as long as two hours. They were filled with water and manually operated, meaning someone had to be there to turn them when their time ran out. Clearly, this was not an efficient means of keeping time, which suggests something else that is obvious: the family wasn't overly concerned about time of day.

The family did not measure time by minutes and hours. Instead, they measured it in turns and short-turns. (When a glass's top portion emptied, it had to be 'turned'.)

A short-turn lasted roughly one minute. These glasses were used to time events of short duration. During the Presider Flamesword Test in Book I, ten small bottles were used to time each test.

A full-turn, or turn, was about an hour, or sixty short-turns. These glasses were used for meetings, classes and as part of the Village Timekeepers. The Timekeepers were made of twelve full-turns. The first four jars would contain blue tinted water. The next four would be clear. The last four would have red tinted water. Most of the villages had a Timekeeper. One of the Unaligned (a servant class people who are not especially keen on their status) would be responsible for turning the glasses.

The family had 440 houses (I counted them - and I know who lives in every one - do I live an exciting life, or what) in 29 settlements, or villages, but not all had a Timekeeper. Only the eighteen largest villages kept one, and very few houses had one. Some of the family Sovereigns, or other weathy members with live-in servants had them.

The large-turn glasses were only used at the temple during classroom instruction.

Regarding timekeeping, the family was far behind other cultures. Even the nearby Kingdom of Azua had better. But, as I said, time of day was not a significant concern to the family. They were warriors, hunters, farmers and herdsman of cattle. Most gauged their time by the position of the sun. At night, it was the moon - when there was one. Even when things were rushed, their lives were slower than ours.

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Tuesday, December 16, 2008

If the Saga's About Madatar, Why Make Khirsha the Main Character

Swords of Fire is about Madatar. It is his story. But he is not the Point of View Character (POVC). Neither is Ardora, the Yin to to his Yang. Instead, the POVC is a character who is young, strong, vulnerable and who has a lot to learn. Why?

Mostly, it felt right. But there are clear advantages in choosing Khirsha over Madatar. The most important being that the reader gets to discover Madatar over time - like all the other characters in Swords of Fire. Until Madatar is revealed (in Book II, if you're interested), we wonder about him. Who is he, really? Why hasn't he revealed himself - to anyone?

There are clues but, like so many clues, they don't appear to be clues until shortly before (or after) their revelation. There were more clues, but I'm being forced to cut some in order to shorten the length of Book I. Even after Madatar is revealed, we are left with things to ponder. Each book in the progression presents new clues, and our knowledge escalates with the conflict until the inevitable final battle. (I haven't written it - officially - but I know what it is.)

Actually, did I say the most important reason for choosing Khirsha instead of Madatar as POVC was to discover Madatar? I'm wrong. The most important reason is that I believe readers can better identify with Khirsha than with Madatar. Khirsha is more like us. He lives in a physical world, as opposed to the spirit realm of Madatar and the Children of Fire. Khirsha is a lot like us - even if he isn't.

Mostly, it felt right. But there are clear advantages in choosing Khirsha over Madatar. The most important being that the reader gets to discover Madatar over time - like all the other characters in Swords of Fire. Until Madatar is revealed (in Book II, if you're interested), we wonder about him. Who is he, really? Why hasn't he revealed himself - to anyone?

There are clues but, like so many clues, they don't appear to be clues until shortly before (or after) their revelation. There were more clues, but I'm being forced to cut some in order to shorten the length of Book I. Even after Madatar is revealed, we are left with things to ponder. Each book in the progression presents new clues, and our knowledge escalates with the conflict until the inevitable final battle. (I haven't written it - officially - but I know what it is.)

Actually, did I say the most important reason for choosing Khirsha instead of Madatar as POVC was to discover Madatar? I'm wrong. The most important reason is that I believe readers can better identify with Khirsha than with Madatar. Khirsha is more like us. He lives in a physical world, as opposed to the spirit realm of Madatar and the Children of Fire. Khirsha is a lot like us - even if he isn't.

Posted by

Bevie

at

4:04 AM

Monday, December 15, 2008

Shatahar

Shatahar is Zenophone's main agent for finding and destroying Madatar, and ultimately Ardora.

He is the most powerful of the Warlords, the strongest of Zenophone's servants. He is so powerful, in fact, that he has designs on usurping his master's position and becoming the Ruling Power over The Great Sea himself. Yet powerful as he is, he is terrified at the prospect of Madatar finding him first. This is his greatest weakness, and the reason he delays his own victory. Fear may be a powerful weapon, but it can also be a two-edged sword.

According to some archival writings, it was Shatahar who first discovered Elva's Children (Elves) and brought a host of Barbarians against them. But the Elves escaped, with the help of the Figgits and their sailing craft. For this reason Shatahar bears an especial hatred for Figgits.

In Pawns (a.k.a. Flames of Hatred), Shatahar makes a cryptic comment regarding Lord Kensington: Time moved forward. Time was his enemy. He was trapped in time, but to be anywhere else was to risk assault. In Time he would crush his enemy. He would crush all who opposed him. Meanwhile, what was he to do? He lacked advantage. It had been taken from him. Curse Kensington! This passage is very likely to disappear from the final version, but it seems to indicate that Kensington is the reason for Shatahar losing whatever advantage he had. It also hints at something Swords of Fire does not make clear until Book III: Time is a place. And, as a place, one can either be in time, or out of it. There were advantages and limitations to both. Regarding what Kensington did, this is what happened:

When the Children of Fire first walked upon the waters they generated a great cloud of condensation. This Cloud remained for the duration of The Great Sea's lifespan. It was held back from all but a few lifeless worlds at the command of Lord Kensington. When the Figgits took the Elves onto the ocean, Kensington released the Cloud and it blanketed all of The Great Sea. Even the Children of Fire had trouble seeing through the Cloud, and Kensington used this to scatter the Elves and hide them from Zenophone, Shatahar and the other Warlords.

Shatahar - and the others who sought Madatar's destruction - now had to begin from scratch, searching the worlds one by one to find their enemy. Since they were all terrified of their foe, this process was slow. Moving from world to world took time. It also took energy, and Shatahar soon learned it was seldom possible for him to enter a world unannounced. The power and anger he projected just could not be contained. The Warlords were hindered by something else: mistrust of their allies. They just did not share information with each other. Neither did Zenophone share with his Warlords. Although allied against a common enemy, the Warlords tended to act independently. This was another of their weaknesses.

Eventually, Shatahar would employ lesser beings than himself, called Titans, to make the world-to-world search. The Titans would travel at Shatahar's bidding, and since Shatahar was gifted more so than the other Warlords in understanding the minds of Kensington and Grenville, the leaders in the effort to help Madatar, Shatahar was able to stumble upon key places in Madatar's rise to power. Fortunately for Madatar, Shatahar didn't understand just how key his information was.

He is the most powerful of the Warlords, the strongest of Zenophone's servants. He is so powerful, in fact, that he has designs on usurping his master's position and becoming the Ruling Power over The Great Sea himself. Yet powerful as he is, he is terrified at the prospect of Madatar finding him first. This is his greatest weakness, and the reason he delays his own victory. Fear may be a powerful weapon, but it can also be a two-edged sword.

According to some archival writings, it was Shatahar who first discovered Elva's Children (Elves) and brought a host of Barbarians against them. But the Elves escaped, with the help of the Figgits and their sailing craft. For this reason Shatahar bears an especial hatred for Figgits.

In Pawns (a.k.a. Flames of Hatred), Shatahar makes a cryptic comment regarding Lord Kensington: Time moved forward. Time was his enemy. He was trapped in time, but to be anywhere else was to risk assault. In Time he would crush his enemy. He would crush all who opposed him. Meanwhile, what was he to do? He lacked advantage. It had been taken from him. Curse Kensington! This passage is very likely to disappear from the final version, but it seems to indicate that Kensington is the reason for Shatahar losing whatever advantage he had. It also hints at something Swords of Fire does not make clear until Book III: Time is a place. And, as a place, one can either be in time, or out of it. There were advantages and limitations to both. Regarding what Kensington did, this is what happened:

When the Children of Fire first walked upon the waters they generated a great cloud of condensation. This Cloud remained for the duration of The Great Sea's lifespan. It was held back from all but a few lifeless worlds at the command of Lord Kensington. When the Figgits took the Elves onto the ocean, Kensington released the Cloud and it blanketed all of The Great Sea. Even the Children of Fire had trouble seeing through the Cloud, and Kensington used this to scatter the Elves and hide them from Zenophone, Shatahar and the other Warlords.

Shatahar - and the others who sought Madatar's destruction - now had to begin from scratch, searching the worlds one by one to find their enemy. Since they were all terrified of their foe, this process was slow. Moving from world to world took time. It also took energy, and Shatahar soon learned it was seldom possible for him to enter a world unannounced. The power and anger he projected just could not be contained. The Warlords were hindered by something else: mistrust of their allies. They just did not share information with each other. Neither did Zenophone share with his Warlords. Although allied against a common enemy, the Warlords tended to act independently. This was another of their weaknesses.

Eventually, Shatahar would employ lesser beings than himself, called Titans, to make the world-to-world search. The Titans would travel at Shatahar's bidding, and since Shatahar was gifted more so than the other Warlords in understanding the minds of Kensington and Grenville, the leaders in the effort to help Madatar, Shatahar was able to stumble upon key places in Madatar's rise to power. Fortunately for Madatar, Shatahar didn't understand just how key his information was.

Sunday, December 14, 2008

The High King - Good or Evil

I suppose the definition of the High King's involvement in The Great Sea depends on one's view of someone who has the power to do anything. Most views of such beings - real or imagined - tend to be prejudiced one way or the other.

Some would hold that, since the High King has the power to stop all evil but doesn't, the High King is himself evil. They maintain that a good being of such power would suppress all evil and keep The Great Sea at peace. But there is a problem with that which the Evil Viewers (those who see the High King as evil, not viewers who are evil) refuse to acknowledge. In order to suppress all evil, the High King (or whoever) would have to suppress all freedom, because the simple truth is - everyone tends to evil. The Evil Viewers deny this, but it is true. All beings, creatures and what have you are inclined to act out of selfish motive. Not only that, but what one being, creature or what have you considers evil, another might consider their 'right', and to be denied that right is evil. You see, it comes down to how one defines evil. Let us look at The Great Sea.

The High King created The Great Sea. It was his to give to whomever he chose. He gave it to the Children of Fire, but with the understanding it was eventually to go to Madatar and Ardora. Until Madatar and Ardora claimed their gift, Kensington was to rule and Draem and Zenophone were to support him. Fair enough.

But in Zenophone's mind, he was far better suited to rule the Sea than Kensington. Furthermore, why should the Sea be given to Madatar and Ardora when they had no part in fashioning it? After all, was it not the Children who did most of the actual work? In Zenophone's mind, it was evil for him to do all of that work and get nothing in reward. It wasn't fair that Madatar and Ardora should be given something for which they had not labored. Evil.

From Kensington's point of view it did not matter that Madatar had not been present. The Sea belonged to the High King and the High King was free to give it to whomever he wished. It could be argued that being given the regency may have influenced Kensington's thinking. Would he have thought the same had Zenophone been chosen as regent? In any case, from Kensington's point of view, refusal to abide by the High King's decision was evil.

But it goes even further than that. The concept of what is evil and what is good filters down into the very basic elements which make up life on the Sea. The mortal beings who have been given free thought - and thus named Free People - have dominion over the creatures which live out their existence by instinct. Horses, sheep, cattle and other creatures are forced to serve Men, Dwarfs and Figgits. Is that fair? What is more, some creatures live by feeding upon others. Is that fair? Some say yes and some say no.

The High King set the rules by allowing certain things to be and not others. Individual concepts of his goodness - or lack of it - derive from a selfish perspective. The free thinking beings considered actions which supported their wants and desires to be good, and those which interfered with them bad. Beasts and other creatures didn't care one way or another. They just lived until they died, and perhaps that is the pivitol point on which good and evil truly separate. There is life, and then there is death. What happens after death? Nothing? Transition? Eternity? What happens?

If, as some claimed, death was the end of whatever/whoever died, then life on The Great Sea was all important, and whatever happened on The Great Sea was all important. So to be denied a good life for no apparent reason was evil.

But what if there was more? What if life on The Great Sea was akin to living in a nursery? What if dying simply meant graduation? That changes things a bit, although there are those who would say not by much. But suddenly, life on The Great Sea becomes a school. Troubles and blessings, whether one's own or another's, are simply lessons to help prepare for what comes next. If so, then why not just say what comes next? Maybe because what comes next is entirely determined by what takes place? It changes things drastically, at least in the minds of some.

Was the High King good or bad? Each reader will make up his/her own mind regarding that, and that is as it should be. Some will express their opinion to others, and that is well and good. Others may even seek to persuade others to believe as they do, which is fine. Some will get angry when others disagree with them. That is unfortunate.

In any case, what is the Author's intent? Well, that would be me. With regard to Swords of Fire, I am the one who has the power to put a stop to anything I choose. Even the High King cannot act apart from my will. As a writer, I make the determination over what is good, what is bad - and what is simply a matter of perspective. When someone reads what I have written, the story becomes their's, and they will make these determinations.

For the record, I believe the High King is good - because he conforms to my idea of goodness. However, even I must concede that he cannot be wholly good, because my idea of goodness tends to be somewhat fluid, changing as I grow in knowledge and experience. It isn't runny, like pure water. It is more like a thick lava crawling across the ground. It will harden in time, but that is not to say a great upheaval cannot change it.

So it is with me. Many of my beliefs regarding good and bad have hardened. Not all. New experience still affects my views on many things, and in some things I have completely reversed my thinking over the years. This is especially so in areas involving punishment and forgiveness. I don't see far, but I see further ahead than I did before. My physical eyes continue to weaken, but my inner eyes, my comprehension, increase, albeit slowly. As I understand better, I can see further ahead - to a point. This is affecting how I view good and bad and punishment and forgiveness. I see myself differently, and so I see others differently. I don't always like what I see in me, but I'm realizing I am so much like everyone else - even if I am so different.

Is the High King good? Of course he is, silly. He is me. How can I see him any other way?

Some would hold that, since the High King has the power to stop all evil but doesn't, the High King is himself evil. They maintain that a good being of such power would suppress all evil and keep The Great Sea at peace. But there is a problem with that which the Evil Viewers (those who see the High King as evil, not viewers who are evil) refuse to acknowledge. In order to suppress all evil, the High King (or whoever) would have to suppress all freedom, because the simple truth is - everyone tends to evil. The Evil Viewers deny this, but it is true. All beings, creatures and what have you are inclined to act out of selfish motive. Not only that, but what one being, creature or what have you considers evil, another might consider their 'right', and to be denied that right is evil. You see, it comes down to how one defines evil. Let us look at The Great Sea.

The High King created The Great Sea. It was his to give to whomever he chose. He gave it to the Children of Fire, but with the understanding it was eventually to go to Madatar and Ardora. Until Madatar and Ardora claimed their gift, Kensington was to rule and Draem and Zenophone were to support him. Fair enough.

But in Zenophone's mind, he was far better suited to rule the Sea than Kensington. Furthermore, why should the Sea be given to Madatar and Ardora when they had no part in fashioning it? After all, was it not the Children who did most of the actual work? In Zenophone's mind, it was evil for him to do all of that work and get nothing in reward. It wasn't fair that Madatar and Ardora should be given something for which they had not labored. Evil.

From Kensington's point of view it did not matter that Madatar had not been present. The Sea belonged to the High King and the High King was free to give it to whomever he wished. It could be argued that being given the regency may have influenced Kensington's thinking. Would he have thought the same had Zenophone been chosen as regent? In any case, from Kensington's point of view, refusal to abide by the High King's decision was evil.

But it goes even further than that. The concept of what is evil and what is good filters down into the very basic elements which make up life on the Sea. The mortal beings who have been given free thought - and thus named Free People - have dominion over the creatures which live out their existence by instinct. Horses, sheep, cattle and other creatures are forced to serve Men, Dwarfs and Figgits. Is that fair? What is more, some creatures live by feeding upon others. Is that fair? Some say yes and some say no.

The High King set the rules by allowing certain things to be and not others. Individual concepts of his goodness - or lack of it - derive from a selfish perspective. The free thinking beings considered actions which supported their wants and desires to be good, and those which interfered with them bad. Beasts and other creatures didn't care one way or another. They just lived until they died, and perhaps that is the pivitol point on which good and evil truly separate. There is life, and then there is death. What happens after death? Nothing? Transition? Eternity? What happens?

If, as some claimed, death was the end of whatever/whoever died, then life on The Great Sea was all important, and whatever happened on The Great Sea was all important. So to be denied a good life for no apparent reason was evil.

But what if there was more? What if life on The Great Sea was akin to living in a nursery? What if dying simply meant graduation? That changes things a bit, although there are those who would say not by much. But suddenly, life on The Great Sea becomes a school. Troubles and blessings, whether one's own or another's, are simply lessons to help prepare for what comes next. If so, then why not just say what comes next? Maybe because what comes next is entirely determined by what takes place? It changes things drastically, at least in the minds of some.

Was the High King good or bad? Each reader will make up his/her own mind regarding that, and that is as it should be. Some will express their opinion to others, and that is well and good. Others may even seek to persuade others to believe as they do, which is fine. Some will get angry when others disagree with them. That is unfortunate.

In any case, what is the Author's intent? Well, that would be me. With regard to Swords of Fire, I am the one who has the power to put a stop to anything I choose. Even the High King cannot act apart from my will. As a writer, I make the determination over what is good, what is bad - and what is simply a matter of perspective. When someone reads what I have written, the story becomes their's, and they will make these determinations.

For the record, I believe the High King is good - because he conforms to my idea of goodness. However, even I must concede that he cannot be wholly good, because my idea of goodness tends to be somewhat fluid, changing as I grow in knowledge and experience. It isn't runny, like pure water. It is more like a thick lava crawling across the ground. It will harden in time, but that is not to say a great upheaval cannot change it.

So it is with me. Many of my beliefs regarding good and bad have hardened. Not all. New experience still affects my views on many things, and in some things I have completely reversed my thinking over the years. This is especially so in areas involving punishment and forgiveness. I don't see far, but I see further ahead than I did before. My physical eyes continue to weaken, but my inner eyes, my comprehension, increase, albeit slowly. As I understand better, I can see further ahead - to a point. This is affecting how I view good and bad and punishment and forgiveness. I see myself differently, and so I see others differently. I don't always like what I see in me, but I'm realizing I am so much like everyone else - even if I am so different.

Is the High King good? Of course he is, silly. He is me. How can I see him any other way?

Saturday, December 13, 2008

Kelso

This is the first of my posts on the people who are important to Khirhsa, who is the Main Character in my Swords of Fire saga. It is only fitting I begin with Kelso, although Kelso is not, ultimately, the most important person to Khirsha.

I can write a awful lot about Kelso (or is that a lot, awfully?), but I will keep this post short. My first novel hasn't been published and I don't want to reveal too much right now.

Kelso is near cousin to Khirhsa, which means there is a sibling relationship between their parents. In the case of Kelso and Khirhsa it is their fathers. Khaiu (Kelso's father) and Shello (Khirsha's father) are brothers. Much is made in Pawns (a.k.a. Flames of Hatred) how Kelso and Khirsha are like brothers. "Different in appearance, they were very much alike in spirit and had bonded closer than many who were married." (from Pawns)

Kelso was born on *Nelshius in the year 329 to Tura and Khaiu. This was the day which separated the Planting Season from the Growing Season. We would call it the beginning of summer. His birth took place at the Great Hall. Hawnka (another important character in Khirsha's life) acted as mid-wife assistant. Khirsha would be born four years later, at Mid-Summer's Day. Kelso's first sibling, Thaia, would not arrive until 337. Khirsha's first sibling, Kaschira, was not born until 338. Both Thaia and Kaschira would die in the Year of Sickness in 340. That was a notable year for many. It was also the year when Khirsha had his first notable contact with Tavaar, who was to become quite important to him. Shirae and Tursa, Khirsha and Kelso's youngest sisters, would not be born until 342. This lack of siblings brought the boys together as though they were brothers, and it remained that way until death finally separated them.

Kelso was pretty much everything a mother and father could want. He was strong, gifted, handsome, intelligent. The list went on. He is described in Pawns as being "built for strength and endurance. He had dark eyes that looked out mischievously through thick black hair hanging loose to his shoulders". Many girls near his age desired him, but he only allowed a few to get close. Partly, this was out of fear. It was the one area in which Kelso's confidence abandoned him. But mostly it was because, like his father, Kelso was intensely interested in developing his skills with the flamesword, and relationships tended to be distracting. The result was he was seen as the greatest warrior of his generation. Possibly even greater than Shello, who many believed to be the greatest ever.

He was Khirsha's mentor in virtually everything, including girls. In Pawns, it is Kelso who opens Khirsha's eyes to the political subterfuge going on around them. It is Kelso who first concludes the family is at risk of war, and with who. It is Kelso who points out to Khirsha that spying on the flying Cere Princess is hardly an act worthy of love. It is Kelso who encourages Khirsha to speak with Sayla before their friendship is ruined. And it is Kelso who prophetically tells Khirsha he is going to have to make a difficult decision of life and death. This position of importance creates a problem.

The problem with Kelso being so important to Khirhsa, both as a pseudo-brother and a mentor, is that Kelso also becomes Khirsha's crutch. As long as Kelso is around, Khirsha will never achieve his potential. This is proven by the fact that Khirsha always loses to Kelso in everything. (An extremely important point.) When they were very young this was only natural. Kelso was four years Khirsha's senior. But by the time Khirsha was nineteen (his age during Pawns) he should have been been able to win at least some time. That he never did was evidence of Kelso's emotional superiority. The two had to separate in order for Khirsha to grow, and that is, in fact, what happens.

Should Pawns ever become a published work, and should you come to read it, pay close attention to Khirsha's interactions with Kelso. They portend a lot.

* The Great Sea's calendar year was 396 days divided into eight months of 48 days each and 12 days which were not part of any month. Each month had six 8-day weeks. Every week day had its own name, and each day of the year was also uniquely named. The year was structured so that every day had the same name every year. Thus, for someone born on Magday Calesen 3 in the year 340, their birthday in 341, 342, 343 and so forth would remain Magday Calesen 3.

The Swords of Fire Calendar

The Swords of Fire Calendar is posted below. The print is small because Blogger is shrinking the image to fit. To read the calendar start at the top left and read across, then down to the left and across again. Thus, Year-In is the first day of the year, followed by Amaris, followed by the six weeks of Calesen, followed by Mid-Spring, followed by the six weeks of Effloren, etc.

Each year had 396 days.

Each year had 396 days.

Friday, December 12, 2008

The Worlds and Their Origins

When the High King created The Great Sea he did not do all of the work himself. He could have, but that is not the way he does things. Instead, he provided the direction and means and allowed the Children of Fire to build it. The King did make the original foundation, and the Fire which sustained the Sea was his. But the actual fashioning was done by the Children of Fire. Think of it as a Master Craftsman handing his students a basic form, such as a ball of clay, and telling them to reshape it into a bird, or a tree, or anything. That is what the High King did.

Some place in the archives (I can't find it now) I have an account of how the first world was created. It was Kensington who made it. He, Draem and Zenophone had just arrived. The Fire in the midst of the ring had already melted much of the ice, and the High King had blown upon the waters to start the rotation. Kensington stepped upon the Sea, and when he lifted his foot, land from beneath the surface, broke free and rose. The three Lords walked the Sea, breaking up more and more pieces of land, and generating a thick steamy cloud in the process. Soon, they were joined by others, and the footprints of their frolicking became the worlds.

The Children watched the worlds (lifeless pieces of earth) race across the waters, crashing, merging and sinking. Eventually, they began pushing the worlds together, creating a massive piece of land which became a vortex to everything else. It was upon this Original World that the High King introduced Life. It was an explosion of life. The waters had life. The land had life. There was life in the air. And the Children were allowed to tend and direct this life, as gardeners and herdsmen.

The Children governed their new world from its center. For time uncounted this continued. Then, at last, Zenophone believed he was ready and made his move to take sole control. And so began The Great War. But Zenophone had miscalculated. His followers did not number so highly as he had deceived himself into believing. Neither did all of the creatures he had made come to him. Only a few dragons took his side, and none of the most powerful. Unwilling to relent, Zenophone chose to see the Great Sea destroyed rather than allow another to have it.

The World was rent apart, killing great numbers of the Sea's life. But before all was lost the High King intervened. Like a parent putting a stop to a fight between siblings which has escalated to a point of danger, the High King ended the War and imposed restrictions on what the Children could, and could not, do henceforth. All who had participated were confined to the Sea, even those who's strength had been exhausted. For them, two isles were made: The Isle of Wonder, for those who had fought beside Kensington and Draem; and The Isle of Nether Gloom, for those who had fought with Zenophone.

The King gave them their decree. "The isles shall beckon to you according to your deeds. When your strength gives way you shall be pulled directly to the isle which holds your heart. From the Isle of Nether Gloom there is no escape. Those who go there will remain in their confinement until I at last put an end to the Sea. On the Isle of Wonder you will rest and regain your strength. When you are able, you will be free to rejoin in the work of repair."

The Children were then tasked with repairing the Sea, in as much as it could be repaired. They were forbidden to rejoin the pieces of their world because the upheaval required would kill the life which remained. So the worlds were left separate. They were hidden from each other by the cloud of mist which still hung over the waters. Each moved over the waters at its own pace, and each had it's own time. The Children built portals, windows from one world to another to allow quick passage. In time, there was a new routine.

But Zenophone was not content. The Sea had been promised to Madatar. What, he thought, if Madatar was not able to claim his prize? What if he were to be so decimated that he was trapped on one of the isles? And so Zenophone, and all who were too proud to return to Kensington, set about to find Madatar and destroy him. It was a dangerous game they played. Madatar was stronger than any one of them, including Zenophone. And should he join with Ardora, there would be no chance of victory. They were limited in what they could do. If they pushed too hard, the High King might intervene again. But for whatever his reasons, the High King was not interfering at the moment. The race was on. Madatar was somewhere on The Great Sea. But on which world?

Some place in the archives (I can't find it now) I have an account of how the first world was created. It was Kensington who made it. He, Draem and Zenophone had just arrived. The Fire in the midst of the ring had already melted much of the ice, and the High King had blown upon the waters to start the rotation. Kensington stepped upon the Sea, and when he lifted his foot, land from beneath the surface, broke free and rose. The three Lords walked the Sea, breaking up more and more pieces of land, and generating a thick steamy cloud in the process. Soon, they were joined by others, and the footprints of their frolicking became the worlds.

The Children watched the worlds (lifeless pieces of earth) race across the waters, crashing, merging and sinking. Eventually, they began pushing the worlds together, creating a massive piece of land which became a vortex to everything else. It was upon this Original World that the High King introduced Life. It was an explosion of life. The waters had life. The land had life. There was life in the air. And the Children were allowed to tend and direct this life, as gardeners and herdsmen.

The Children governed their new world from its center. For time uncounted this continued. Then, at last, Zenophone believed he was ready and made his move to take sole control. And so began The Great War. But Zenophone had miscalculated. His followers did not number so highly as he had deceived himself into believing. Neither did all of the creatures he had made come to him. Only a few dragons took his side, and none of the most powerful. Unwilling to relent, Zenophone chose to see the Great Sea destroyed rather than allow another to have it.

The World was rent apart, killing great numbers of the Sea's life. But before all was lost the High King intervened. Like a parent putting a stop to a fight between siblings which has escalated to a point of danger, the High King ended the War and imposed restrictions on what the Children could, and could not, do henceforth. All who had participated were confined to the Sea, even those who's strength had been exhausted. For them, two isles were made: The Isle of Wonder, for those who had fought beside Kensington and Draem; and The Isle of Nether Gloom, for those who had fought with Zenophone.

The King gave them their decree. "The isles shall beckon to you according to your deeds. When your strength gives way you shall be pulled directly to the isle which holds your heart. From the Isle of Nether Gloom there is no escape. Those who go there will remain in their confinement until I at last put an end to the Sea. On the Isle of Wonder you will rest and regain your strength. When you are able, you will be free to rejoin in the work of repair."

The Children were then tasked with repairing the Sea, in as much as it could be repaired. They were forbidden to rejoin the pieces of their world because the upheaval required would kill the life which remained. So the worlds were left separate. They were hidden from each other by the cloud of mist which still hung over the waters. Each moved over the waters at its own pace, and each had it's own time. The Children built portals, windows from one world to another to allow quick passage. In time, there was a new routine.

But Zenophone was not content. The Sea had been promised to Madatar. What, he thought, if Madatar was not able to claim his prize? What if he were to be so decimated that he was trapped on one of the isles? And so Zenophone, and all who were too proud to return to Kensington, set about to find Madatar and destroy him. It was a dangerous game they played. Madatar was stronger than any one of them, including Zenophone. And should he join with Ardora, there would be no chance of victory. They were limited in what they could do. If they pushed too hard, the High King might intervene again. But for whatever his reasons, the High King was not interfering at the moment. The race was on. Madatar was somewhere on The Great Sea. But on which world?

Thursday, December 11, 2008

The Phoenix and The Dark Birds

There is very little in the archives regarding Phoenix. They were created especially by Lord Kensington as a means to heal the hurts and ills which resulted from the natural course of being alive on the Great Sea. For nesting places, Kensington created the Pillars, of which Fire Mountain was significant in Pawns (how's that for a rename of Flames of Hatred?). After that, I haven't written much about them.

It seems strange that I have so little information about the Phoenix. After all, they are creatures of Fire, and Fire is all-important in Swords of Fire. Fire is the means by which life continues. It is representative of a life form's power. It is who they are.

The Phoenix lived in peace during the Early Time, the time before the Great War. They were shy creatures, but everyone knew of them, and should special healing be needed, petitions would go forth for Lord Kensington to send one of his precious Phoenix. What was not known was that Lord Zenophone had created his own version, which he named Dark Bird.

Whereas Phoenix gave of themselves in order to heal others and lived in light, Dark Birds devoured and lived in shadow. This made them a particular danger to Phoenix, and in the Great War the Dark Birds made a close end to them. After the war, the Phoenix were not to be found. Fortunately, not only had Zenophone made few Dark Birds, but without the Phoenix to feed upon, the Dark Birds also dwindled.

It seems strange that I have so little information about the Phoenix. After all, they are creatures of Fire, and Fire is all-important in Swords of Fire. Fire is the means by which life continues. It is representative of a life form's power. It is who they are.

The Phoenix lived in peace during the Early Time, the time before the Great War. They were shy creatures, but everyone knew of them, and should special healing be needed, petitions would go forth for Lord Kensington to send one of his precious Phoenix. What was not known was that Lord Zenophone had created his own version, which he named Dark Bird.

Whereas Phoenix gave of themselves in order to heal others and lived in light, Dark Birds devoured and lived in shadow. This made them a particular danger to Phoenix, and in the Great War the Dark Birds made a close end to them. After the war, the Phoenix were not to be found. Fortunately, not only had Zenophone made few Dark Birds, but without the Phoenix to feed upon, the Dark Birds also dwindled.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

The Elves

The Elves were not listed in my posting "The Free People" because at the beginning there were no Elves. The Elves were the result of the union between Massimo, last of the Nomads, and Elva, last of the Pennans.

There is an unfinished story of how Massimo was captured by Barbarians. His tribe was wiped out. He was taken as a gladiator, to fight for the amusement of others in a circus environment. While at his prison he met Elva, who had also been taken prisoner. Her task was to provide musical entertainment. With them was Hondu, last of the Mortals, who's task it was to perform 'magic' tricks. (Mortals were Children of Fire who had taken mortal form in order to help the various Races recover from the Great War. Hondu had chosen to be a Figgit.) Hondu had the power to free himself whenever he wanted, but he was waiting. When Massimo arrived, he knew what he was waiting for and arranged for Elva and Massimo to escape with him. Pursued by Barbarians, Hondu led Elva and Massimo into the mountains where, at long last, Hondu's mortality came to an end. Before he died he gave the power he had accumulated evenly to Elva and Massimo, thereby binding them as wife and husband. He also was able to arrange their escape from the world.

When Elva and Massimo reached their new world they remained in hiding. Hondu had warned them they were not only at risk from Barbarians. Should the Warlords learn the significance of their union, they would seek their deaths. (Warlords were Children of Fire. They were powerful beings who sought to take control of the Sea.) So they lived on the slopes of a mountain range, and there they had their children, and their children had their children. The children called themselves, Elva's Children. Over time this became shortened to Elva's, and eventually Elves.

What made Elva and Massimo's union so special was Hondu's giving them his Power. The Mortals were granted the knowledge of when they would die. Shortly before death they would 'pass on' their Power to another Mortal. This resulted in a consolidation of Power until, finally, Hondu had all of the Power of all of the Mortals. Hondu gave this to Elva and Massimo, knowing that by doing so, he had made the decision on where Madatar would come from.

Eventually, as the Elves' population increased, the Warlords did come to notice them, and they did understand the significance of their origins. And so began the Warlords' persecution of the Elves. Their fear of Madatar hindered their efforts, and because of that the Elves survived. Eventually, they would become scattered across the Sea, awaiting the coming of Madatar. For some, the years had been few when Madatar finally came. For others, it had been so long they had forgotten about him.

There is an unfinished story of how Massimo was captured by Barbarians. His tribe was wiped out. He was taken as a gladiator, to fight for the amusement of others in a circus environment. While at his prison he met Elva, who had also been taken prisoner. Her task was to provide musical entertainment. With them was Hondu, last of the Mortals, who's task it was to perform 'magic' tricks. (Mortals were Children of Fire who had taken mortal form in order to help the various Races recover from the Great War. Hondu had chosen to be a Figgit.) Hondu had the power to free himself whenever he wanted, but he was waiting. When Massimo arrived, he knew what he was waiting for and arranged for Elva and Massimo to escape with him. Pursued by Barbarians, Hondu led Elva and Massimo into the mountains where, at long last, Hondu's mortality came to an end. Before he died he gave the power he had accumulated evenly to Elva and Massimo, thereby binding them as wife and husband. He also was able to arrange their escape from the world.

When Elva and Massimo reached their new world they remained in hiding. Hondu had warned them they were not only at risk from Barbarians. Should the Warlords learn the significance of their union, they would seek their deaths. (Warlords were Children of Fire. They were powerful beings who sought to take control of the Sea.) So they lived on the slopes of a mountain range, and there they had their children, and their children had their children. The children called themselves, Elva's Children. Over time this became shortened to Elva's, and eventually Elves.

What made Elva and Massimo's union so special was Hondu's giving them his Power. The Mortals were granted the knowledge of when they would die. Shortly before death they would 'pass on' their Power to another Mortal. This resulted in a consolidation of Power until, finally, Hondu had all of the Power of all of the Mortals. Hondu gave this to Elva and Massimo, knowing that by doing so, he had made the decision on where Madatar would come from.

Eventually, as the Elves' population increased, the Warlords did come to notice them, and they did understand the significance of their origins. And so began the Warlords' persecution of the Elves. Their fear of Madatar hindered their efforts, and because of that the Elves survived. Eventually, they would become scattered across the Sea, awaiting the coming of Madatar. For some, the years had been few when Madatar finally came. For others, it had been so long they had forgotten about him.

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

Madatar and Ardora

Madatar was part of the original creation - both mine, and the High King's. Who and what he was grew as I continued to write until he became the one for whom the Great Sea was created.

Ardora is a more recent, but logical, creation - mine, NOT the High King's. Ardora began when Madatar began. She is the compliment to Madatar - the Yin to his Yang.

Madatar and Ardora are also beings of Fire. Spirits, if you will, but of a different order than the other Children of Fire. Individually, they became more powerful than any other on the Great Sea, save the High King himself. Collectively, they became more powerful than everyone, and everything, combined on the Great Sea, save the High King. But they are not together.

Shortly after the Great Sea's creation, Zenophone and his followers attempted to take the Great Sea for their own. Ultimately this resulted in the Great War, in which the Sea itself was nearly destroyed. It was at this time Madatar and Ardora were separated and hid from each other. For while they were destined to become the reigning power over the Great Sea, they had yet to achieve that stature. In the early days of the Sea's history they were vulnerable. So the High King hid them, and not even Kensington knew where.

Why would the High King separate them? It is not always easy to know the thoughts of the High King. But this we know: Even at the Beginning, Madatar nor Ardora did not have the power to defeat Zenophone and his followers. However, together their growth would cause ripples across the Sea which would only draw their enemies to them. Separated, the ripples became confused with all else that was taking place.

That is the story of Swords of Fire. It is the saga of Madatar and Ardora's search for each other and their ultimate battle with Zenophone and his followers. It is presented from the perspective of one Khirsha, son of Klarissa and Shello, of the Line of Swords, in the House of Jora. Khirsha became the eye of the storm, so to speak.

Ardora is a more recent, but logical, creation - mine, NOT the High King's. Ardora began when Madatar began. She is the compliment to Madatar - the Yin to his Yang.

Madatar and Ardora are also beings of Fire. Spirits, if you will, but of a different order than the other Children of Fire. Individually, they became more powerful than any other on the Great Sea, save the High King himself. Collectively, they became more powerful than everyone, and everything, combined on the Great Sea, save the High King. But they are not together.

Shortly after the Great Sea's creation, Zenophone and his followers attempted to take the Great Sea for their own. Ultimately this resulted in the Great War, in which the Sea itself was nearly destroyed. It was at this time Madatar and Ardora were separated and hid from each other. For while they were destined to become the reigning power over the Great Sea, they had yet to achieve that stature. In the early days of the Sea's history they were vulnerable. So the High King hid them, and not even Kensington knew where.

Why would the High King separate them? It is not always easy to know the thoughts of the High King. But this we know: Even at the Beginning, Madatar nor Ardora did not have the power to defeat Zenophone and his followers. However, together their growth would cause ripples across the Sea which would only draw their enemies to them. Separated, the ripples became confused with all else that was taking place.

That is the story of Swords of Fire. It is the saga of Madatar and Ardora's search for each other and their ultimate battle with Zenophone and his followers. It is presented from the perspective of one Khirsha, son of Klarissa and Shello, of the Line of Swords, in the House of Jora. Khirsha became the eye of the storm, so to speak.

Posted by

Bevie

at

1:48 AM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

High King,

Madatar-Ardora,

Saga Elements

Monday, December 8, 2008

Lord Kensington

Kensington was the "chief" of all the Children of Fire who came to the Great Sea. My original thought was that Kensington was to rule the Sea but, as I stated in the previous post, that quickly changed.

In Flames of Hatred, Shatahar's servant, Vitchkl, makes a reference to Kensington's Pillar. The meaning of this odd statement is not given in Flames of Hatred, although I suspect attentive readers are able to figure it out through context. I will spell it out plainly: Kensington's Pillar is Fire Mountain, the place where the family gets the ore to create flameswords. In fact, the ore's power is Kensington's power. There is more to it, but that is essentially it.

Kensington created the pillars as nesting pods for the Phoenix, which he also created. The Phoenix had the power of healing, but they were weakened in doling it out. The pillars allowed them to renew their strength quickly, although that was not the Phoenix's sole source of renewal. All creatures took renewal from the Fire which was at the Sea's midst. They called it the sun, but it was much more than that.

Not all worlds had a pillar, and at the time of Flames of Hatred the Phoenix are considered mythological because few, if any, survived the Great War which nearly destroyed the Sea.

Kensington was in command of The Cloud, the mystical place between worlds in which Time had little or no power. He also was in charge of monitoring and moving the Regulator of Time, which was the real age of the Sea. He was in charge of it, but he only moved it at the High King's command.

Neither the Cloud nor the Regulator of Time come into play in Flames of Hatred. The Cloud is seen for the first time in Book II, The Prophecies of Madatar, and the Regulator of Time is referenced in Book III, Bonds of Love. I believe it is Book III in which we get to meet Lord Kensington.

In Flames of Hatred, Shatahar's servant, Vitchkl, makes a reference to Kensington's Pillar. The meaning of this odd statement is not given in Flames of Hatred, although I suspect attentive readers are able to figure it out through context. I will spell it out plainly: Kensington's Pillar is Fire Mountain, the place where the family gets the ore to create flameswords. In fact, the ore's power is Kensington's power. There is more to it, but that is essentially it.

Kensington created the pillars as nesting pods for the Phoenix, which he also created. The Phoenix had the power of healing, but they were weakened in doling it out. The pillars allowed them to renew their strength quickly, although that was not the Phoenix's sole source of renewal. All creatures took renewal from the Fire which was at the Sea's midst. They called it the sun, but it was much more than that.

Not all worlds had a pillar, and at the time of Flames of Hatred the Phoenix are considered mythological because few, if any, survived the Great War which nearly destroyed the Sea.

Kensington was in command of The Cloud, the mystical place between worlds in which Time had little or no power. He also was in charge of monitoring and moving the Regulator of Time, which was the real age of the Sea. He was in charge of it, but he only moved it at the High King's command.

Neither the Cloud nor the Regulator of Time come into play in Flames of Hatred. The Cloud is seen for the first time in Book II, The Prophecies of Madatar, and the Regulator of Time is referenced in Book III, Bonds of Love. I believe it is Book III in which we get to meet Lord Kensington.

Posted by

Bevie

at

5:37 PM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

High King,

Mythological Creatures,

Phoenix

Thursday, December 4, 2008

Lords #1

The role of the Children of Fire changed over time. Originally, control of the Sea was to be given to one of the Three Lords. That plan ended when the Lords initiated the War which nearly destroyed the Sea. Then the Children of Fire became regents for the Free People, who would be granted final dominion.

That was the original concept. Subsequent exploration shows it to be inaccurate. The Great Sea was always meant for Madatar and Ardora.

There is not a lot written about the Three Lords at this time. Most of what is known about them is still in my head. I did come across some archival records, written nearly thirty years ago, which sheds some light on who the Lords were, and what their role was. The following is the result of combining several documents into one record. Please forgive the overly dramatic prose.

There were three (3): Kensington, Draem and Zenophone. They were the first of the Children of Fire to come to the Great Sea. They were also the most powerful of those who came. That there were more powerful members of their order seems to be implied by means of their limited abilities. However, on the Great Sea there were only two (2) powers mightier: Madatar - when joined with Ardora; the High King himself.

"Kensington, Draem and Zenophone were ever known by the Free Peoples as The Lords. These were chosen for the powers which they represented.

Kensington cherished wisdom and understanding above all else. His delight was in the search for knowledge and truth.

Draem loved beauty and order. She believed in the good of existence and purpose. To Draem, nothing was ugly and nothing was meaningless.

Zenophone believed in strength. Without strength, mortal beings could not survive. Their wisdom would fade, their beauty abandon them, and their purpose be short-lived."

Kensington is credited with bringing the first land to the surface.

"And the Three came to the Great Sea together. They saw it and marveled at its wonder and beauty. Then Kensington stepped upon the still melting ice, and his step caused the ice to flee, and land, freed from its prison, rose in its place. This would be where they would begin."

Each of the Three Lords is credited with the creation of certain mythological creatures, although they all had a part in the creation of all. The following list is NOT all-inclusive.

Kensington's creatures: Phoenix, Winged Horses, Gryphons

Draem's creatures: Golden Sheep, Giant Cats, Unicorns

Zenophone's creatures: Dragons, Centaurs

That was the original concept. Subsequent exploration shows it to be inaccurate. The Great Sea was always meant for Madatar and Ardora.

There is not a lot written about the Three Lords at this time. Most of what is known about them is still in my head. I did come across some archival records, written nearly thirty years ago, which sheds some light on who the Lords were, and what their role was. The following is the result of combining several documents into one record. Please forgive the overly dramatic prose.

There were three (3): Kensington, Draem and Zenophone. They were the first of the Children of Fire to come to the Great Sea. They were also the most powerful of those who came. That there were more powerful members of their order seems to be implied by means of their limited abilities. However, on the Great Sea there were only two (2) powers mightier: Madatar - when joined with Ardora; the High King himself.

"Kensington, Draem and Zenophone were ever known by the Free Peoples as The Lords. These were chosen for the powers which they represented.

Kensington cherished wisdom and understanding above all else. His delight was in the search for knowledge and truth.

Draem loved beauty and order. She believed in the good of existence and purpose. To Draem, nothing was ugly and nothing was meaningless.

Zenophone believed in strength. Without strength, mortal beings could not survive. Their wisdom would fade, their beauty abandon them, and their purpose be short-lived."

Kensington is credited with bringing the first land to the surface.

"And the Three came to the Great Sea together. They saw it and marveled at its wonder and beauty. Then Kensington stepped upon the still melting ice, and his step caused the ice to flee, and land, freed from its prison, rose in its place. This would be where they would begin."

Each of the Three Lords is credited with the creation of certain mythological creatures, although they all had a part in the creation of all. The following list is NOT all-inclusive.

Kensington's creatures: Phoenix, Winged Horses, Gryphons

Draem's creatures: Golden Sheep, Giant Cats, Unicorns

Zenophone's creatures: Dragons, Centaurs

Posted by

Bevie

at

2:01 PM

Labels:

Children of Fire,

Dragons,

Mythological Creatures,

Unicorns

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Today's Music

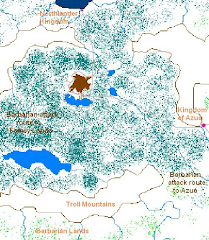

Yeah. That's The Great Sea all right.